Driven by nostalgia for times that never were, victimised by foes that never existed, and waiting for an enlightened leader who never arrives: most political thinkers of Latin America have perfected the art of the blame game. The continent’s permanent state of underdevelopment is everyone’s fault – from ignorant colonial powers to arrogant Yankees and heartless capitalists.

Driven by nostalgia for times that never were, victimised by foes that never existed, and waiting for an enlightened leader who never arrives: most political thinkers of Latin America have perfected the art of the blame game. The continent’s permanent state of underdevelopment is everyone’s fault – from ignorant colonial powers to arrogant Yankees and heartless capitalists.

The Manual of the Perfect Latin American Fool (1996)1, and The Return of the Fool (2007)2, expose the Latin American left for what it is: a collection of bleeding hearts seeking solace and refuge in a heady mix of nationalism and socialism preferably served up by a strongman such as Juan Domingo Perón, Getúlio Vargas, or Fidel Castro.

Both bestselling books are the product of a counterculture that coalesced around Peruvian author and Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa who has long battled to expose the internal contradictions and retrograde values of Latin America’s much-admired intellectual elite of armchair socialists.

The two fool books primarily aim to debunk the collection of celebrated myths pushed by the recently deceased Uruguayan journalist and writer Eduardo Galeano whose The Open Veins of Latin America (1971)3 conveniently attributes the continent’s many ills to centuries of exploitation. The book is still considered the bible of the Latin American left.

However, just before his death, Mr Galeano admitted that he was unable to revisit his magnum opus. Speaking at the II Biennial Book Fair of Brasília in 2014, the writer confessed that Open Veins was more a product of revolutionary fervour than of proper historic research: “At the time, my intellectual thought processes had not yet fully formed.”

Hence, the fool.

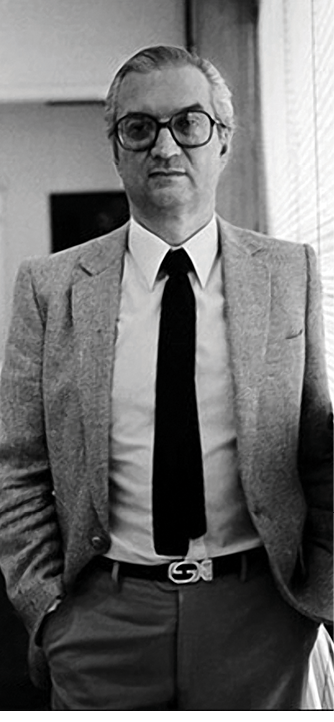

Before Mario Vargas Llosa rose to fame in the 1990s, Mr Galeano’s nemesis was the Venezuelan journalist, diplomat, and philosopher Carlos Enrique Rangel (1929-1988), an early and vocal critic of the left’s tendency to don the cloak of victimhood. In particular, Mr Rangel disassembled the myth of the noble savage whose carefree existence was swiftly brought to an end by European colonisers.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the tale of the noble savage caused furore all over Europe. Sailors returning from the New World brought with them stories of people living in earthly paradise. They spoke of societies without rulers, soldiers, slaves, money, disease and – most importantly – want. Surrounded by natural abundance, these noble savages had no need for work and were all about play as nature readily satisfied all their needs.

The myth of the noble savage resonated throughout the Old World at a time when monarchs and clerics held absolute power, hunger and pestilence decimated populations, and the life of most commoners was still largely untouched by the renaissance.

Eduardo Galeano, and the generation of intellectuals he inspired, argued that European conquerors saw in the noble savage a direct threat to their rule. No society should be allowed to flourish in the absence of kings and cardinals, and of taxes and tithes. Thus, they immediately set out to destroy the noble savage and subject him to the sword and the holy book.

While the myth of the noble savage was soon forgotten – or stamped out – in Europe, it lived on in Latin America where visions of paradise lost mobilised tens of thousands of young people into the ranks of guerrilla armies in the 1960s and 1970s. They took up arms to try break the continent’s bonds with its colonisers and their descendants or agents.

In From Noble Savage to Good Revolutionary (1976)4 Carlos Rangel credits the legend of the Noble Savage – his destruction by evil powers and the resulting yoke an entire continent was condemned to carry forever after – with keeping Latin America from joining modern times and tapping into its potential. While Mr Rangel does not dismiss the many wrongs perpetrated by the colonisers, he flatly refuses to accept these injustices as an excuse for underdevelopment. The cult of the victim, he argues, has wrought a new character – that of the good revolutionary who promotes nationalism, protectionism, authoritarianism, and “caudillismo,” the typically Latin American preference for patriarchal strongmen who set the vectors of national policy while keeping order.

Carlos Rangel points out that the causes pursued by the good revolutionary are the same ones as those that motivated pre-Columbian rulers – no pussies either – colonisers, and the self-serving elites that took over when Spanish and Portuguese rule was ended in the early to mid-1800s. Mr Rangel also argued that due to its cultural background and roots, Latin America would be well-advised to recognise and assume its place amongst western nations. The notion that the continent somehow constitutes an entity onto its former self – the yearning for a return to the days of the noble savage – is an abomination that, according to Mr Rangel, has cast Latin America adrift into a cultural limbo.

Not knowing what it is, results in not knowing where it wants to go – i.e. Latin America is held back by an identity crisis of continental proportions.

References

- Manual del perfecto idiota latinoamericano by Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza, Carlos Alberto Montaner, and Álvaro Vargas Llosa (1996, Editora Plaza & Janés) – ISBN: 978-0-5530-6060-0).

- El regreso del idiota by Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza, Carlos Alberto Montaner, and Álvaro Vargas Llosa with an introduction by Mario Vargas Llosa (2007, Editora Debate) – ISBN: 978-0-3073-9151-3)

- Las venas abiertas de América Latina by Eduardo Galeano (2009 reprint, Editora Siglo XXI) – ISBN: 978-8-4323-1145-1)

- Del buen salvaje al buen revolucionario by Carlos Enrique Rangel Guevara (1976, Monte Ávila Editores) – ISBN: 978-8-4377-0049-3.