JASON AGNEW reports on SDG8 — decent work and economic growth — in his ongoing series for BV

SDG8: DECENT WORK AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

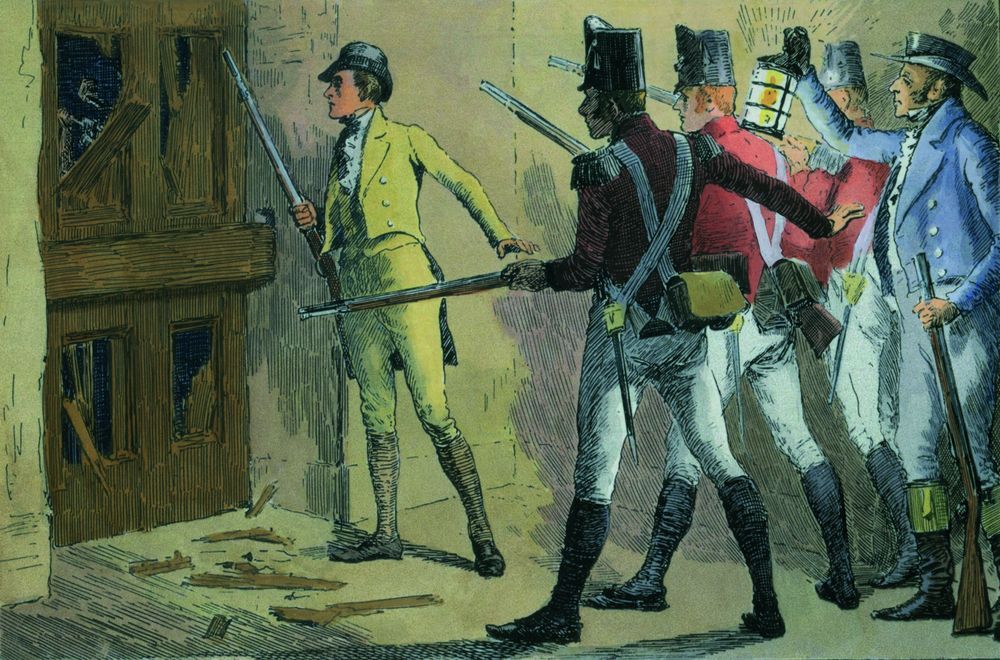

On March 11, 1811, government troops broke up a crowd of protestors in the textile-manufacturing town of Nottingham in the English midlands.

That night, the workers — who had been demanding more work opportunities and higher wages — broke into mills in the nearby village of Arnold and smashed spinning and weaving machines. Similar attacks soon spread across Britain’s industrial heartlands.

The government, terrified that this could become a national movement just 20 years after the French Revolution, positioned thousands of soldiers to defend factories. Parliament hurriedly introduced a law to make machine-breaking punishable by death.

The protestors’ leader was a man named Ned Ludd, who — like his predecessor in the local fight for social justice, Robin Hood — purportedly lived in Sherwood Forest.

But these workers were not, as the modern usage of Luddite implies, opposed to machinery per se; many of them were skilled machine operators. They railed against what they saw as “a fraudulent and deceitful manner” of circumventing standard labour practices.

Kevin Binfield, editor of the 2004 collection Writings of the Luddites, confirms this: “They just wanted machines that made high-quality goods and they wanted these machines to be operated by workers who had gone through an apprenticeship, and got paid decent wages.”

Sound familiar?

The UN’s SDG8 aims to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all”. Given the times we live in, the website now makes reference to Covid-19 and the implications for employment during and after the pandemic.

It rightly points out that global economic growth was already slowing before Covid (BC, if you like) and that the two percent GDP per capita growth between 2010 and 2018 had fallen to 1.5 percent in 2019. That there was growth at all is largely down to developing countries; advanced economies such as France and Italy have experienced virtually none since the turn of the millennium. People in the rust belt of the US and post-industrial parts of the UK have seen a 30 percent fall in real income over the last 30 years, arguably leading to the rise of populist phenomena such as Trump and Brexit.

On March 20, 2020, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a pandemic lockdown. In just one day, some 100,000 migrant workers and day labourers fled the city of Mumbai and returned to their villages, where at least they would eat. These unprotected labourers, mostly from the impoverished northern states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, had kept the city going by cleaning drains, constructing buildings, driving the city’s 250,000 auto-rickshaws and keeping office workers fed.

The government suspended all public transport in and out of the city — which led to a mass exodus on foot. Desperate people walked off with their meagre possessions — and possibly Covid — rather than risk starvation on the deserted streets of the Island City.

As the UN’s website warns, “During the pandemic, 1.6 billion workers in the informal economy risk losing their livelihoods.” That illustrates all too starkly that while these people have made a valuable contribution to sustainable economic growth, they certainly haven’t enjoyed decent working conditions.

And now, from the Luddites to the present day. The agricultural and industrial revolutions led to a concentration of wealth. In 2021, there is justifiable fear that the technological revolution will do the same — and more rapidly.

It is leading to a shift from skilled manufacturing jobs to insecure employment in call centres or e-commerce warehouses. As once-secure jobs in banks and manufacturing disappear, society must adapt to new working practices such as zero-hour contracts, unpaid holidays, and no sick pay.

The term “McJob” was coined by sociologist Amitai Etzioni in The Washington Post in 1986. It was popularised by Douglas Coupland’s 1991 novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. McJobs are “low-pay, low-prestige, low-dignity, low benefit, no-future job in the service sector”. Frequently, Coupland noted, they were “considered a satisfying career choice by people who have never held one”.

McJob was added to Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary in 2003 and while the fast food company threatened to sue, it never did. McDonald’s argues that 20 of its top 50 managers started off flipping burgers.

SDG8, more than most, doesn’t seem quite sure what it wants. Some would argue that sustainable economic growth is an oxymoron, and that the relentless focus on GDP is killing the planet. “Decent” work is a relative concept, and some may prefer menial jobs to wearing a suit and commuting to a stuffy office.

What has been made clear by the pandemic is that the vast disparity in working conditions — in different countries and within societies — will continue to expand. We are once more witnessing an increase in social unrest as technology concentrates wealth in the hands of the few at the expense of the many.