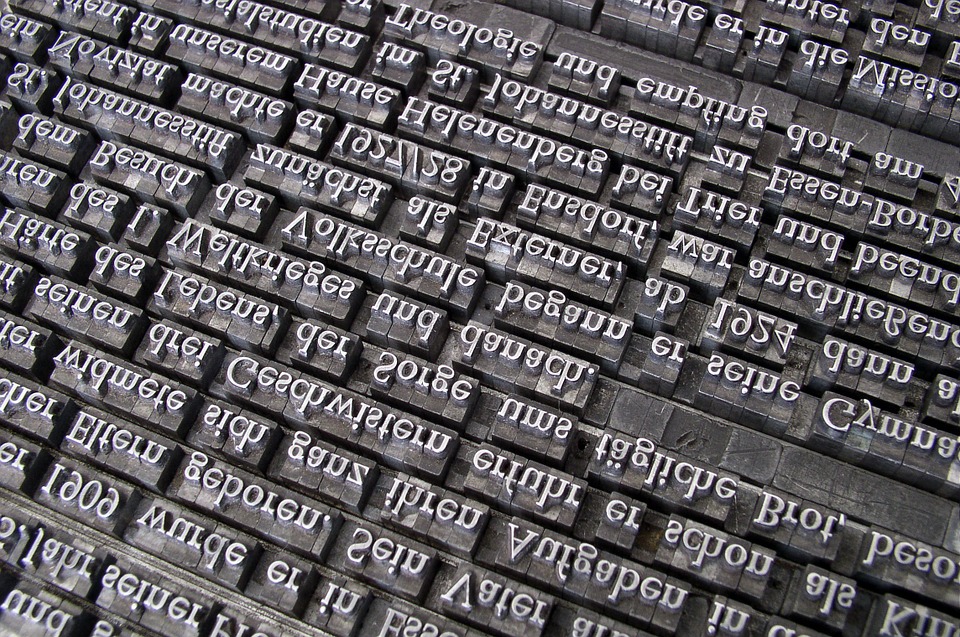

Bold headlines, fast-paced storytelling, illustrations aplenty, and a scoop in every issue: Hak Holdert knew precisely what a newspaper should look like in order to sell. Born into a family of printers, the young Holdert learned the trade at his uncle’s printing plant in Amsterdam. Soon, however, Hak Holdert struck out on his own, opening a printer’s shop in 1894.

With a keen eye for opportunity, a good sense for business, and a roster of moneyed friends, the young printer managed to acquire the twin papers De Telegraaf and De Courant after their founder has passed away in 1902. Whilst De Courant widely read and, as such, a solid money maker, its smaller but more interesting sibling had been subjected to frequent tinkering – with mixed results. The paper had rallied with all its might to the Afrikaner cause during South Africa’s Boer War, supporting Paul Kruger in his fight against the British.

After hostilities ceased, and looking for ways to attract new readers, De Telegraaf launched a wildly popular children’s edition published by Swawa Helgi, fairy-in-chief, and her mysteriously nameless riddle-editor. Both kept up a public correspondence during which magic objects changed hands and adventures in mythical lands unfolded.

Whilst appreciating the readership, Hak Holdert did not quite trust the editors behind the children’s edition. Fearing they could fly the coop, he provoked an argument and promptly fired both. Mr Holdert also failed to appreciate the boundless optimism that characterised De Telegraaf at the time. He had little interest in praising whatever civic initiative was deemed fashionable.

Editorial Drives Profits

Changing course, Hak Holdert determined that profit should come before all else and be preferably the product of editorial engagement with whomever happens to be in power or is likely to arrive at the top shortly.

Fast forward a century or so, and little has changed. Though now mature and since time immemorial the largest-circulation newspaper in The Netherlands, De Telegraaf remains at heart a campaign newspaper, throwing its considerable weight behind whatever cause seems worthwhile and winning. Staunchly conservative during the roaring sixties and the progressive 1970s, the paper tentatively switched sides in the mid-1980s, embracing the environment and a modest degree of multiculturalism. An early supporter of LBGT rights, De Telegraaf won lavish praise even from those who had despised the paper earlier for its vehement denunciation of everything left of centre.

Bridging the Divide

The formula first implemented by Hak Holdert and expanded upon by a string of highly professional and visionary editors-in-chief, De Telegraaf uniquely and expertly managed to bridge the divide that separates creaming tabloids from gentlemanly broadsheets.

The product of a typically Dutch yearning for pragmatism and compromise, De Telegraaf possesses both the punch of a tabloid and the depth of a paper of record. Its financial section is mandatory reading for anyone with an interest in markets and business. Until a decade ago, the paper maintained a global network of staff correspondents – mostly erudite classicists and established writers – feeding the newsroom a stream of exclusive features on often esoteric topics broached nowhere else.

At the Apex

Flashy and serious at the same time, and with an editorial budget no other Dutch media outlet could hope to match, De Telegraaf offered its readers – close to 900,000 by the early 2000s – a diverse mix of stories available nowhere else. Others took note of its formula. When in 1981 Gannett Company, a US media conglomerate and at the time publisher of twenty regional and metro papers, decided to launch a national newspaper, it turned to De Telegraaf for the required expertise of how to manufacture a quick, yet deep and engaging, read and assemble pages with an enhanced pull factor.

It all revolves around the ability to deliver a knockout blow without appearing to do so. Get the reader hooked not with a shout, but by surprise. Generations of Telegraaf editors have been trained on the job in a setting that requires wit, stamina, and – most of all – a little bit of knowledge about everything under the proverbial sun. Acquiring the right tone – striking a fine balance between sensation and sense – was of paramount importance: without it no editor could hope to reach the top.

Notwithstanding its proprietary editorial formula – tried and tested since the early 1900s – De Telegraaf was woefully late to adapt to changing times. Alone at the top and without a competitor in sight, the newspaper eventually grew complacent. By going mainstream, it lost the magic touch: no longer guaranteed to surprise – or cause a delightful and delectable scandal – De Telegraaf also let go of its corporate ferocity.

Always managed by journalists, and consistently turning a sizeable profit regardless market conditions, De Telegraaf usually made mincemeat out of upstarts that proved too audacious – and did so in short order. In 1999, the publishers of Metro, a Swedish tabloid freely distributed amongst commuters, decided to expand their operation to The Netherlands, they soon discovered that disruptors are seldom wise to dominant player head on. The news hit the powers-that-be at the Amsterdam Basisweg not unlike a tonne of bricks. Who had ever heard of such a preposterous proposition? Giving away newspapers – for free.

Though it took a while for De Telegraaf management to process the shock, it responded in style by launching its own free newspaper on the exact same date Metro was to celebrate its Dutch debut. Flush with ready cash, De Telegraaf promptly decided to do one better and expand into Sweden to combat the evil at its source.

Retreat

That, however, was the last fight De Telegraaf would win. Largely a victim of its own success, management deployed its formidable war chest to acquire newspapers wherever one was to be found for sale. Prevented for political reasons to bid on its rival national papers, De Telegraaf gobbled up provincial broadsheets almost by the dozen, patching together a rather disjointed network of media interests without much scope for either economies of scale or synergies.

Having arrived late online, De Telegraaf burned through the remaining corporate reserves buying up websites without much concern for quality or sustainability. Most failed miserably as Internet bubbles burst to make way for mobile computing, social networking, or whatever next Big Thing.

De Telegraaf consistently arrived late at the scene where only the rejects and misfits were still up for sale. In the end, the paper’s demise was sealed when in 2004 the journalists were ousted from upper management by disgruntled shareholders who promptly called in the bean counters – assorted administrators and business managers with no clue about the editorial product or its legacy.

Whilst De Telegraaf still rules the Dutch print media scene, its power and impact have waned considerably. Circulation has plummeted and now hovers around 450,000 copies. Slashed newsroom budgets and reduced staffing levels – mandated by MBA-toting managers with their eye on the bottom line instead of the product sold – have all but ensured that the decline is irreversible.

What’s Next

As such, De Telegraaf’s recent history – and travails – only shows that Hak Holdert was right all along: for a newspaper to be and remain successful it needs both a vision and the determination to pursue it – regardless of collateral damage caused.

However, the last editor-in-chief (2009-2015) who tried to return the paper to its profitable roots, Sjuul Paradijs – combative, acerbic, arrogant, and a brilliant journalist with an eye for news that sells – was invited to step down after he rocked the boat too hard, causing concern amongst younger journalists less inclined to put up a fight for editorial independence and out-of-the-box reporting. He was replaced by the affable Paul Jansen who toes the line. Mr Holdert would not have appreciated that. If it is a license to print money you want, some guts are called for.

Still, it would be a serious mistake to write De Telegraaf off as a remnant from a bygone era, destined to wither away into obscurity. The paper’s editorial formula remains as unique today as it was before. As a company, the newspaper possesses the expertise to stage a comeback – perhaps not as much in print, but as a force to be reckoned with on other (online) platforms.

In fact, the paper could do worse than leverage its editorial prowess in order to boost both reach and profits. An editorial powerhouse first and foremost – and one built around a newsroom – De Telegraaf lost its sense of purpose when the company pursued diversification and became a media conglomerate instead of a news company – downplaying in the process its greatest asset: an editorial formula that, even after 123 years, remains highly innovative.