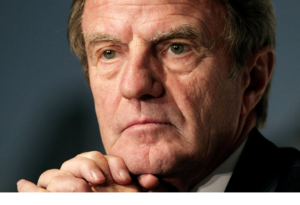

Humanitarian, activist, doctor, and politician: Bernard Kouchner is an outspoken advocate for the duty of states to intervene in other countries in order to prevent humanitarian crises and further the spread of human rights. Dr Kouchner is no stranger to heroism, danger, and controversy. His iconoclastic approach has won admirers and acolytes, although his promotion of le droit d’ingérence (the right to intervene) involving military assets has come under increasing scrutiny post 9/11.

Humanitarian, activist, doctor, and politician: Bernard Kouchner is an outspoken advocate for the duty of states to intervene in other countries in order to prevent humanitarian crises and further the spread of human rights. Dr Kouchner is no stranger to heroism, danger, and controversy. His iconoclastic approach has won admirers and acolytes, although his promotion of le droit d’ingérence (the right to intervene) involving military assets has come under increasing scrutiny post 9/11.

Dr Kouchner was born in Avignon, France, two months after the outbreak of the Second World War. His father’s parents were murdered in Auschwitz. Dr Kouchner has said that it was the Holocaust, perpetrated on the soil of supposedly civilised Europe, which fuelled a sense of urgency that brought him to humanitarian work. Seeing children starve while employed in Biafra as a young doctor during Nigeria’s 1968 civil war caused Dr Kouchner to dedicate his life to the prevention of humanitarian crises.

As a student he was active in left wing politics, as per Winston Churchill’s suggestion. Dr Kouchner manned the barricades surrounding the Sorbonne University in the Quartier Latin during the May 1968 Paris student revolt. A few months later, he answered a call from the International Red Cross for medics to go to Biafra, the breakaway province that was locked in a savage battle for independence from Nigeria. The two doctors, two clinicians, and two nurses dispatched by the ICRC were shocked at the viciousness of the conflict as they set about providing medical relief at hospitals targeted by Nigerian armed forces.

Since the International Committee of the Red Cross is committed to maintaining strict political and religious neutrality, Dr Kouchner and his colleague Dr Recamier felt that the world needed a more activist entity to tell the world about the systematic targeting of civilians by military forces. They openly criticised the Nigerian government – and the Red Cross – for their apparent complicity.

Back in Paris, a group of doctors began to lay the foundations for a new and more proactive form of humanitarianism that would ignore political or religious boundaries and prioritise the welfare of those suffering.

Dr Kouchner: “We wanted to ensure sufficient knowledge of this new type of medicine: war surgery, triage medicine, public health, education, etcetera. It’s simple really: go where the patients are. It seems obvious, but at the time it was a revolutionary concept because borders got in the way.”

Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) was created in December 1971 with a staff of 300 doctors, nurses and other professionals. Its credo was the belief that all people have the right to medical care regardless of gender, race, religion, or political affiliation, and that the needs of these people outweigh the need to respect national boundaries.

MSF’s first mission was to Managua in 1972 where an earthquake had destroyed most of the city and killed tens of thousands. Two years later, it set up a relief mission in Honduras after thousands were killed by major flooding. In 1975, MSF established its first large-scale programme providing medical care for fleeing Cambodians seeking sanctuary from the genocidal Pol Pot regime.

As the years went by, MSF found itself increasingly torn between the natural progression of becoming institutionalised as an organisation able to cope with large scale crises and the more romantic notion of being an agile commando unit of emergency doctors. Dr Kouchner favoured the latter, but in 1979 MSF voted in favour of formalising its structure. Dr Kouchner left to found Médecins du Monde (Doctors of the World).

During the 1980s, Dr Kouchner organised a number of operations assisting refugees across the globe. He also became increasingly involved in mainstream French politics. As a high-profile member of the Socialist Party he was the Minister of State from 1988 to 1991 and became the Minister of Health in 1992. He went on to take a seat in the European Parliament and before long was elected to the presidency of its standing committee on Development and Cooperation. In July 1999, Dr Kouchner was appointed Special Representative of the Secretary General of the United Nations and Head of the UN Mission in Kosovo.

Dr Kouchner was one of only a select few French politicians to come out in favour of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, saying his distaste for Saddam Hussein’s regime overcame his dislike of war. In 2007, he was made French Minister of Foreign and European Affairs in the government of President Nicolas Sarkozy, whereupon he was expelled from the Socialist Party.

Dr Kourchner has led a full and fearless life, throwing himself into danger and brushing aside bureaucracy. His belief that morality cannot stop at borders – i.e. that when confronted with extreme wickedness, politics should be sans frontiers – has become widely accepted. Events in the 21st century have seen this philosophy hijacked by politicians. However, Dr Kourchner’s legacy constitutes a lasting contribution to the delivery of humanitarian aid by whatever means necessary.