Africa needs investment to advance sustainable development and see the continent prosper. James Zhan, Astrit Sulstarova and Mathabo le Roux argue that the nature and volume of foreign investment flows into the continent over the past fifteen years show Africa is firmly on the development track.

Africa needs investment to advance sustainable development and see the continent prosper. James Zhan, Astrit Sulstarova and Mathabo le Roux argue that the nature and volume of foreign investment flows into the continent over the past fifteen years show Africa is firmly on the development track.

Global foreign direct investment (FDI) in recent years has been anaemic. In four of the seven years since the global financial crisis, growth has been negative, and on the occasion that it swung into positive territory the level of growth has been unremarkable.

The trend seems incongruous in the face of historically high levels of corporate cash on balance sheets. It is estimated that multinational corporations are flush with more than a collective $5 trillion in cash, yet they have little inclination to spend their cash. The reluctance is explained by the convergence of a set of risk-propelling factors.

On the economic side, the end of the commodities super-cycle, market volatility and weak demand in mature markets are throttling investor confidence, while heightened geopolitical risk, security concerns and the migration crisis are reinforcing political insecurity, adding to the gloom. This sclerosis has raised the spectre that cross-border investment flows may well consolidate at levels that are structurally lower than those before the crisis creating a perfect storm for the global economy.

Fresh figures showing strong FDI growth for 2015 therefore brought welcome respite. UNCTAD’ Global Investment Trends Monitor provisional data for 2015, released at the end of January, show global FDI flows surged 36 per cent – a pace last seen in 2007 – to an estimated $1.7 trillion. While the level stays shy of volumes scaled pre-crisis it is welcome diversion from the course investment has been on for most of the past decade.

On closer scrutiny, however, last year’s rise in FDI flows did not translate into equivalent expansion in productive capacity because cross-border merger and acquisitions (M&As) accounted for the lion’s share of the increase, rather than greenfield investments in new productive assets.

The Wrong Kind of FDI Growth

Cross-border M&As rose 61%, the highest value since 2007, with multinationals taking advantage of their record cash positions, as well as exceptional global liquidity conditions to scoop up prized assets. By contrast, greenfield project announcements, which are indicative of MNEs’ capital expenditure intentions, remained largely flat. And in developing regions where the need for expanded productive capacity is particularly pressing, project announcements in fact declined sharply, notably in Africa (-19%), and Latin America and the Caribbean (-23%).

Another worrying phenomenon is the sizeable part of FDI flows last year that was related to so-called inversion deals – a strategy by which firms acquire a foreign company and the latter is transformed into new headquarters, with the aim to lower the tax burden – and to reconfigurations of corporate structures. This generally results in large movements of capital showing up in the financial account of the balance of payment but with little movement in actual resources.

On the whole the data therefore gives little cause for optimism. The circular character of the predominant part of current investment is particularly troubling given the enormous financing needs for sustainable development, highlighted in UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2014.

The report quantified the annual investment shortfall in developing countries at $2.5 trillion – a gap that can only reasonably be plugged by private sector FDI. In seeking to catalyse this kind of investment UNCTAD has been driving public-private sector dialogue through its World Investment Forum. This year takes the Forum to Africa, the continent where development needs are particularly acute, beckoning the question how the continent has fared in the investment stakes.

Investment Sharply Down Where Most Needed

Africa has been something of a shining star on the economic front in recent years, but in 2015 investment went off course. Inflows fell dramatically, by 31%, to an estimated $38 billion, largely spurred by an investment slump in Sub-Saharan Africa. Central Africa and Southern Africa saw the largest declines in large part as a result of falling demand and rock-bottom commodity prices. Flows into gas-rich Mozambique were down 21% to $3.8 billion. Nigeria saw its FDI decline by 27% to an estimated $3.4 billion as the country was hit by the drop in oil prices. FDI into South Africa fell precipitously, down 74% to $1.5 billion.

Coming in the very year the international community announced the agenda that will direct development ambitions over the next fifteen years, the slump in developing country investment figures signals bleak prospects for its delivery in regions where needs are greatest. Yet, an analysis of the longer-term investment trends on the continent discloses a more encouraging picture with pockets of real progress, giving rise for optimism.

Not All Doon and Gloom

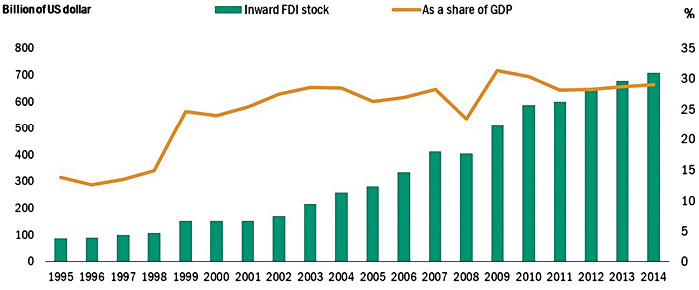

According to UNCTAD data foreign investment in Africa over the past fifteen has increased more than fivefold, reaching $54 billion in 2014 compared to an underwhelming $10 billion in 2000. This has hiked Africa’s share of global flows to 4.4%, which while still modest, is a handsome improvement on the 0.7% in 2000. With more than $700 billion worth of FDI stock, Africa’s FDI performance has, in fact, outpaced its economic expansion, growing by 5% relative to its GDP between 2000 (at 24% of GDP) to 2014 (29%).

While the biggest beneficiaries of FDI historically have tended to be large economies with considerable mineral resources, in recent years, more vulnerable economies, such as Tanzania, Uganda, Madagascar, and Ethiopia, have seen investment flowing in, with intra-regional FDI a particularly significant source of foreign capital in these countries. The senders of FDI to Africa are similarly evolving.

Most FDI stock on the continent are still held by developed country-based parents, but developing country multinationals have had their appetites whetted by Africa, resulting in a spate of investments by Asian emerging economies – notably China, Singapore, Malaysia and India – on the continent in recent years. These new players now largely target assets relinquished by developed country MNEs, as the latter continue their exit from Africa.

Going At It Alone

An even more arresting development has been the acceleration of intra-regional FDI, which lends concrete support to African leaders’ efforts to achieve deeper regional integration. The rapid economic growth of the last decade has underpinned the rising dynamism of African firms on the continent, both on the trade and investment front. Intra-African investments have been fast rising, spurred mostly by the growing expansion of South African firms into the continent. And since 2008 Kenyan, Nigerian, and North African firms have also started venturing cross-border. In fact, between 2009 and 2014, the share of cross-border greenfield investment projects originating from within Africa rose to 19% of the total, from less than 10% in the period 2003 – 2008.

But by far the most encouraging development over the past fifteen years has been the increasingly diverse nature of the investment going into Africa. A growing chorus has been urging Africa to move beyond the mere export of raw materials pointing that manufacturing ability and technology can facilitate high value-added trade for African countries. Not only would this help create employment and raise incomes; it would also help shield developing countries better against cyclical downturns, as witnessed by the current commodity slump, which is wreaking havoc in commodity-dependent developing country markets.

The good news is that FDI into Africa now is helping to drive that transition. Investment into the continent is now more diverse than ever before, driven by demographic developments, high urbanisation rates, improved macroeconomic management, and greater interest from developing economy investors.

Services Up

Services — which increased fourfold between 2001 and 2012 — now constitute the largest part of African FDI stock (48%). Another bright spot is manufacturing. The sharp increase in the number of Asian manufacturers engaging in Africa, as well as new investments from North America and Europe in R&D and consumer industries, gives impetus for the development of regional value chains and the diversification of domestic economies. And, confirming that Africa is truly on the rise, consumer-oriented sectors are now beginning to drive FDI growth.

Expectations for further sustained economic and population growth underlie investors’ continued interest in consumer market-oriented sectors that target the rising middle-class population. This group is estimated to have expanded 30% over the past decade, reaching 120 million people. Targeted industries include consumer products such as food, information technology, tourism, finance and retail. Similarly, driven by growing trade and consumer markets, infrastructure FDI have seen robust increases in information and communication technology and in transport.

Prospects for the continent are muted in the mid-term — as can only be expected in view of the current commodity downturn and a consequent depression in commodity-seeking FDI. But what has been built up over the past fifteen years will not be undone by the downturn, and the continent can expect to continue building economic muscle. Akin to the rise of Asia, which released of millions of people from the poverty trap over the time frame of the Millennium Development Goals, the aspiration is to similarly set Africa on a growth path that will deliver commensurate benefits for its population. The best way to ensure this happens, is to encourage the growth of deeper, and pro-development investment on the continent. i

About the Authors

James Zhan is director of Investment and Enterprise at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and leads the team that produces the World Investment Report

Astrit Sulstarova is chief of the division’s Investment Trends and Data Section.

Mathabo le Roux is economic officer in the Office of the Director.