Corporate emissions-reduction targets have become commonplace. In 2014, 80% of companies that reported their emissions to CDP, an international NGO that holds the largest collection of corporate emissions data, also reported targets for cutting their emissions. These targets vary significantly in scope, structure, and ambition. But at the COP21 climate negotiations in Paris, it was announced that many companies are taking corporate climate commitments much further.

The Science Based Targets initiative announced that 114 major companies committed to set science-based emissions-reduction targets. In other words, they agreed to set targets based on the global emissions cuts scientists say are necessary to prevent the worst impacts of climate change.

Collectively, these companies have annual emissions of at least 476 million tonnes CO2 – equivalent to the annual emissions of South Africa, or 125 coal-fired power plants. They represent approximately $932 billion in total combined profits – greater than the GDP of Indonesia. Their commitments are unprecedented, as never before has such a large group of companies agreed to set targets with the level of ambition dictated by science. This sets a new standard for corporate climate action.

Science-Based Target Setting

Corporate emissions targets are considered science-based if they are in line with the level of emissions reductions necessary to keep global temperature increase well below 2°C (3.6°F) compared to pre-industrial temperatures.

The international community has considered 2°C to be the threshold for warming before sea rise, drought, wildfires, extreme weather events, and other effects of climate change pose catastrophic consequences for the world’s people and economies. In fact, many researchers believe that 2°C is still too risky, so the Paris Agreement that resulted from the COP21 climate meeting was written to include an aspirational goal to limit warming to 1.5°C.

This threshold implies a carbon budget – a total volume of greenhouse gases that can be emitted while still providing a degree of confidence that the target can be met. Research shows that the world has already used more than half of this budget, and if emissions continue unabated, we’re set to burn through the rest in only thirty years. To stay within budget, global emissions must be cut by as much as 72% by 2050.

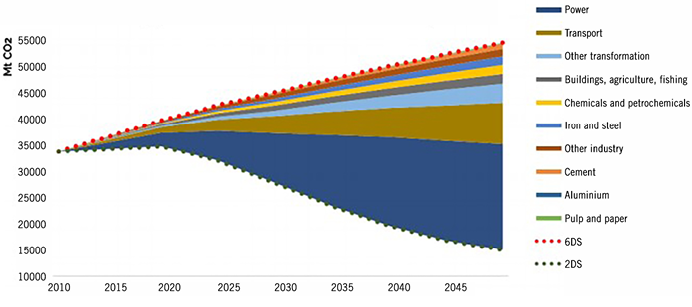

The International Energy Agency has modelled how every major emitting industrial sector must cut emissions (see figure). The model poses serious implications for companies. To do their part – and safeguard their future growth – most companies will have to radically transform their business models, energy use, and energy procurement.

A long-term, science-based emissions target can be a guiding light for companies in the transition to the low-carbon economy. To create one, companies can use various existing methodologies that allocate the global carbon budget at the company level, while accounting for specific characteristics such as emissions rate and expected annual growth.

The Science Based Targets initiative, a joint effort of CDP, the World Resources Institute (WRI), World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and the UN Global Compact, works with companies to set science-based emissions targets. All proposed targets are reviewed for conformity with the initiative’s credibility criteria. As of December 2015, ten companies had emissions targets approved by the initiative: Coca-Cola Enterprises, Dell, Enel, General Mills, Kellogg, NRG Energy, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Sony, and Thalys. Combined, these companies plan to save 799 million tonnes of CO2, equal to preventing the burning of 1.86 billion barrels of oil.

Examples of Science-Based Emissions Targets

Coca-Cola Enterprises: Coca-Cola Enterprises committed to reduce absolute greenhouse gas emissions from its core business operations 50% below 2007 levels by 2020. The company also pledged to reduce emissions from its drinks 33 percent by 2020, using a 2007 base year.

Dell: Dell committed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from their facilities and logistics operations 50% below 2010 levels by 2020, as well as decrease the energy intensity of it product portfolio 80% below 2011 levels by 2020.

General Mills: General Mills committed to reduce absolute emissions 28% across its entire value chain – from farm to fork to landfill – by 2025, using a 2010 base year.

Why Science-Based Targets?

Warming above 2°C would pose serious physical danger to people, wildlife and crops, as well as pose a serious threat to the economy.

The Institute for Policy Integrity recently surveyed 365 economists with knowledge of climate impacts: 42% of them said that it is “extremely likely” that climate change will have a long-term, negative impact on the growth rate of the global economy, while 36% said it is “likely.”

Many business leaders are starting to see how the consequences of climate change will materialise in their own industry. For example, ten CEOs from major food and beverage brands signed a joint letter in October 2015 to advocate for a strong agreement at the COP21 climate negotiation in Paris. As the letter explained, “climate change is bad for farmers and agriculture. Drought, flooding, and hotter growing conditions threaten the world’s food supply and contribute to food insecurity.”

At the same time, a growing amount of research indicates the positive impact that reducing emissions can have on financial performance. CDP analysis shows that companies with published emissions-reduction targets delivered a better return on invested capital over a 12-month period compared to those with no targets. Retail giant Wal-Mart Stores recently announced that it successfully decoupled growth from emissions after exceeding its goal to reduce emissions from its supply chain by twenty metric million tons.

Many companies can enjoy significant cost savings through their low-carbon investments. WWF and CDP’s 3% Solution Report projects that by setting science-based targets, the US corporate sector alone would generate cumulative savings of up to $780 billion by 2020.

In addition, ambitious emissions-reduction targets can open the door to new financial opportunities by driving innovation in products and technologies, creating unique ways to source materials, and expanding into new markets. Today, the global market for low-carbon goods and services is worth more than $5.5 trillion and is growing at 3% per year. The smartest companies are already examining how to shrink the carbon footprint of not just their energy purchases, but also the products in their portfolio, ensuring growth in an increasingly decarbonised market.

The renewable energy industry, for example, has taken root and thrived in response to the need for low-carbon energy. Twenty-five years ago, electricity from renewable sources cost three to four times more than that generated from fossil fuels. Since then, costs have dropped considerably, and most energy sources being developed today are renewable.

The power sector faces similar opportunities. According to a joint report between Accenture and CDP, five low-carbon business models could enable the worldwide electricity sector to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions while enjoying €135 to €225 billion cost savings and €110 to €155 billion in new revenue by 2030.

Why Now?

Companies that commit now to meaningful emissions cuts can enjoy significant cost savings and position themselves ahead of their peers in the low-carbon economy. But delaying action would require more aggressive and costly emissions cuts in the future in order to stay within the carbon budget, posing potentially insurmountable financial shocks.

Findings from the 3% Solution report show that in order to meet the carbon budget, US businesses must reduce emissions 3% annually through 2020. If they do so, they can collectively capture cost-savings of up to $190 billion in 2020, and put us on the pathway to curbing climate change. However, if companies wait until 2020 to begin making significant emissions reductions, they’ll need to cut emissions by 9.7% annually on average – requiring costly and highly disruptive operational changes.

For these reasons, investors are increasingly concerned with their exposure to greenhouse gas emissions and many are already working to decarbonize their investments. The Portfolio Decarbonisation Coalition, a group of institutional investors committed to gradually decarbonising their portfolios, announced during COP21 that it had grown to 25 members, including Allianz and ABP, representing $600 billion in assets under management. The initiative explains that to decarbonise their portfolios, investors may withdraw capital from carbon-intensive companies, invest in low-carbon companies, and engage with portfolio companies to motivate emissions reductions.

Also during COP21, the Financial Stability Board, an organisation that works with financial authorities to strengthen global financial systems, announced a new Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, chaired by former NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg. The task force aims to improve company disclosure of climate-related risk for lenders, insurers, investors, and other stakeholders.

Changing regulations and public policy provide additional compelling reasons for business leaders to pursue ambitious emissions cuts now. The Paris Agreement has asserted a global goal to limit warming to no more than 2°C and preferably no more than 1.5°C. This will require near-term peaking of global emissions followed by rapid decarbonisation, achieving carbon neutrality in the second half of the century.

Nearly 200 countries representing over 90% of global greenhouse gas emissions have submitted climate action plans, many entailing significant emission reductions. The Paris Agreement mandates greater transparency of national emissions and renewed, increasingly ambitious national climate plans every five years.

In order to execute the global climate agreement, world governments will employ new regulations and policies to accelerate the transition to the low-carbon economy. Some are considering putting a price on carbon; the Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition now has 21 national and subnational government members from both the developed and developing world. For companies, planning for ambitious emissions reductions now can mean staying ahead of these future policies and regulations and enjoying a competitive edge over competitors who choose to delay action.

The science is clear: We must reduce our greenhouse gas emissions significantly if we are to spare ourselves, our children, and our economies from the harshest consequences of climate change. The recent momentum around climate action from entities around the world and across sectors demonstrates a great will to decarbonise our world. In order to smoothly transition to the low-carbon economy and gain long-term competitive advantage, companies must set their course now. The methodologies exist for setting an emissions target that aligns with climate science – it’s time for visionary, forward-thinking leaders to act.