The government of Sudan declared Jan Pronk persona non grata in October 2006, summoning the UN special envoy to pack his bags and leave the country in a hurry. His predecessor had met the same fate.

The government of Sudan declared Jan Pronk persona non grata in October 2006, summoning the UN special envoy to pack his bags and leave the country in a hurry. His predecessor had met the same fate.

Mr Pronk had been instrumental in bringing about the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the government of Sudan and the Peoples Liberation Movement. Signed in January 2005, the deal was intended to bring an end to a civil war which had lasted more than two decades and had become the longest lasting civil war in Africa since decolonisation. It also had the highest number of casualties. However, the agreement failed to hold and the fighting continued.

Upon his expulsion from Sudan, Mr Pronk returned to The Netherlands, hoping to resume his career in politics by standing for election as chairman of the Labour Party (PvdA – Partij van de Arbeid). In the 1980s and 1990s, Mr Pronk had served in a number of cabinets of Labour-led coalitions. He lost his bid for power but was awarded a consolation prize and was named chair of the committee charged with the drafting of the party’s programme the European elections of 2009. He left the party four years later, saying that it had strayed too far from its social democratic roots.

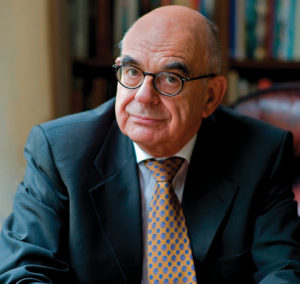

Interested in sustainable development long since before the time the concept became fashionable, Mr Pronk has made a career out of development issues and conflict resolution. Whenever his Labour Party was relegated to the opposition, Mr Pronk would pull up stakes and depart for the international scene, leveraging the power of his Rolodex. Now retired from public life, without all that much to show for it, Mr Pronk managed to secure a position as professor emeritus at the International Institute of Social Studies in The Hague where he imparts the Theory and Practice of International Development.

Mr Pronk studied Economic at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam. After a short spell as a research assistant, he entered politics in the early 1970s. A rising star of the New Left, more akin to a meteorite, he was appointed Minister for Development Cooperation in 1973. Mr Pronk immediately set out to change the fundamentals of the development cooperation policies he inherited.

Mr Pronk’s fata morgana was to equally distribute power and wealth in the world. The New International Economic Order he excitedly pursued would allow developing countries to become self-reliant. He awarded large chunks of his aid budget to Cuba and North Yemen. Mr Pronk was also an active supporter of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa.

By the early 1980s and to the relief of many, he left Dutch politics to become deputy secretary general of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in Geneva. He returned home in the late 1980s and by 1989 again headed the Ministry for Development Cooperation. He promptly picked a fight with Indonesia by criticising, rather loudly, that country’s human rights record. Ever since, Indonesia has refused to accept development aid from the Netherlands.

Mr Pronk’s aims for international development are admirable: his work in Sudan included not just brokering peace, but also the return of displaced people; the disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration of combatants; the clearance of landmines; the monitoring of human rights; the organisation of national elections; and, economic reconstruction and development. However, notwithstanding Mr Pronk’s many good intentions and his mastery of development theory, realities on the ground proved a nut too hard to crack.

He is also the personification of a guilt and angst-driven do-gooder who failed to impress at home and was promptly dispatched far afield to flog policy ideas deemed ill-suited for domestic consumption. Mr Pronk departed with gusto and held a succession of prestigious posts abroad. Between 1973 and 1977, while still a member of the Dutch cabinet, he was deputy governor of the World Bank. After leaving office in 1998, Mr Pronk presided over the United Nations’ climate negotiations and from 2008 to 2011 he presided over the Society for International Development (SID).

During those years, he also chaired the Ecumenical Peace Council in the Netherlands (IKV – Interkerkelijk Vredesberaad) which was later discovered to have been a front organisation of the East German Stasi secret police. Since 2009, Mr Pronk has been a visiting professor at the United Nations University for Peace in Costa Rica. In between, he also managed to push Suriname out of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, brazenly bribing that country with billions to accept the independence it did not at the time desire.

A life-long left winger committed to the field of human development, Mr Pronk may now look back on a long and varied career. While he was able to exert influence both at home and abroad, his track record is a chequered one. Arguably, his political idealism outpaced his achievements.