In a bid to encapsulate the complex challenges global warming poses to businesses and modern society, TONY LENNOX goes down the pub

There’s a painted sign above the door of The Boat Inn, a riverside pub in the Ironbridge Gorge, Shropshire, which reads: “Unspoilt by Progress”. Look more closely at the tide marks on the wall, and one can tell that it has been spoilt by something else — the adjacent River Severn.

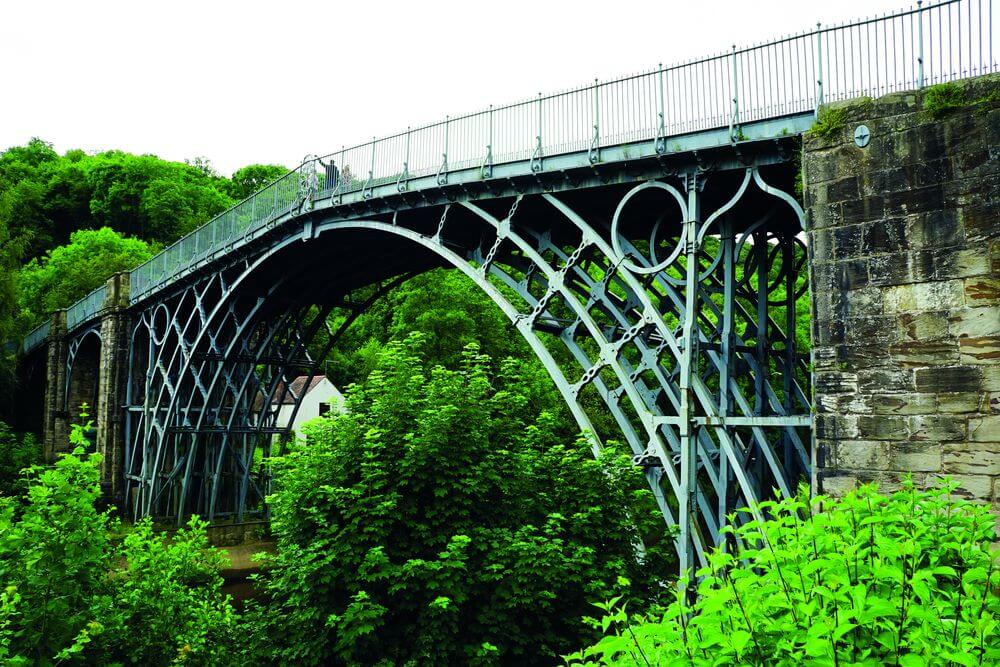

This is an irony which isn’t lost on climate campaigners. The Boat opened its doors in 1740 to serve booming Coalbrookdale, the teeming hive of forges and furnaces which gave birth to the Industrial Revolution. What began in this isolated wooded gorge in the English Midlands spread across the globe. Within a couple of centuries, mankind was pumping noxious fumes into the skies above almost every nation in every continent.

In November 2000, after a miserable summer, the skies turned black over the Welsh hills. The rains swelled the tributaries of the Severn, the surge gathering force as it swept through Shropshire and Worcestershire. It swamped the towns and villages of the Severn Valley. It wasn’t the first flood to devastate homes and businesses in the region, but it was the worst in living memory and, said some, it was man-made.

Earlier that year, catastrophic floods in Mozambique on an entirely greater scale than Shropshire’s had left thousands homeless and 700 people dead. While the threat of climate change had been known for some time, the apparent increase of extreme weather episodes was causing alarm across the planet.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), set up by the UN in 1985, studies the impact of human-induced climate change and examines options for adaptation and mitigation. But attempts by governments to adopt a united front in the face of the challenge have been dogged by controversy and disagreement, including Donald Trump’s notorious assertion that climate change was a hoax.

While environmentalists say the planet’s only hope is to drastically reduce the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, there has been a recent, perceptible change in attitudes in some quarters. If global warming is happening, we need to learn to adapt, and live with it, they say.

A dichotomy is developing between environmentalists and those who see a potential gain in adapting to a changing climate. It has already been suggested, darkly in some quarters, that Russia’s initially sluggish response to the Kyoto agreement may have had something to do with the fact that warming could have a positive effect on a frozen Siberia. Similarly, Canada and Greenland stand to be net-gainers in the win-or-lose stakes as the ice retreats.

In the hotter, poorer quarters of the world, the devastation caused by flood, drought and heat is critical, damaging already unstable economies, putting millions at risk of death and homelessness and potentially provoking mass migration. There will be winners and losers in the great climate shift. The question is: How much will the losers lose, and how big is the prize for the winners?

While it is still the case that the nations of the globe are active, to a greater or lesser extent, in trying to reduce the effect of man-made climate change, there is a growing tendency, among economists — if not environmentalists — to accept that change is happening, and that the world should be preparing to adapt rather than trying vainly to turn the tide. There is a profit incentive in the production of greenhouse gas-reducing technology, and there are plenty of inventors, engineers and entrepreneurs poised to take advantage — an example being the growth of alternative energy production: wind, wave and solar.

Plans to double the size of the world’s biggest offshore wind farm in the Thames estuary have been blocked by conservationists worried about its effect on sea birds. Meanwhile, a few miles away, more than 800 acres of Kent farmland is about to be blanketed by a vast solar farm, causing anguish to nature lovers at the loss of natural habitat. The pursuit of sustainable energy comes at a price.

But while the hand-wringing continues, there is evidence everywhere of change — some of it encouraging. Bertrand Piccard, the first man to fly around the world in a solar-powered aircraft and the founder of the Solar Impulse Foundation, has launched the World Alliance for Efficient Solutions. This organisation aims to identify and catalogue one thousand profitable climate-change solutions and then match them with regions, governments and, most critically, private sector investors.

Swiss national Picard says: “Stop speaking about the problems, start speaking about the solutions. I love when people tell me it’s impossible. [The project] will attract pioneers. They are people who want to innovate, they want to create a new business case.”

An example is the world’s automotive industry, which is moving rapidly towards an electric future. Many car-makers are also racing to develop lighter, more efficient vehicles, using modern materials to replace steel. Tesla Motors vice-president, Jack Pell, says: “The industry has been talking about using different materials for years, and now it has no choice. You are seeing a domino effect as the industry educates itself.”

Entrepreneurs thinking of diving into the climate change industry need to understand that there are risks as well as opportunities. Californian company, Solyndra, which designed and manufactured a radical new solar panel, raised millions from state and private investors on the promise of growth in the solar energy industry. It collapsed in 2012 owing $500 million to the public purse. The problem with Solyndra was that while its technology was cutting-edge, its costs were old-school. Customers found that the Chinese were producing similar products at a fraction of the price, and headed east.

McKenzie Funk, the author of Windfall: The Booming Business of Global Warming, says: “The business community has a real vested interest in understanding reality. I was surprised by how much the big oil companies, for instance, had not just thought about climate change but also put it into their business calculations.”

Critics say that the people best positioned to profit from climate change are the ones most responsible for causing it — the already wealthy in the developed West. So is this a callous response from global business? Not necessarily. According to Funk, politicians have chosen to do little or nothing about climate change. Business is acting partly because political action has overwhelmingly failed.

So, whether it’s insurance companies devising new, lucrative policies to keep wealthy clients safe in the face of extreme weather events, or onshore and offshore wind farm proliferation, or farmland going under acres of solar panels, the business of climate change is booming.

The “Unspoilt by Progress” sign is still above the entrance to the Boat Inn in Coalbrookdale where, these days, they have developed rapid coping strategies to deal with regular floods. Whether the world manages to remain unspoilt by the progress of climate change technology is another question.