Which mixes better with water: electricity or oil? RICHARD THOMAS finds some sea legs in his BV trousers and sets forth to investigate.

WHENEVER the notion of an electric boat is mooted, social media comics pipe up with, “Electricity and water don’t mix.”

These humorous net denizens are obviously unaware that before the nuclear era, all submarines were diesel-electric: diesel for propulsion and battery charging on the surface, electric propulsion while under it. Now, with the rise of electric cars, buses and trucks, there are entire websites devoted to the world of electric boats. One site takes a dig at the critics with the tagline: “Because oil and water don’t mix”.

From luxury motor yachts and speedboats to two-seat inflatables and jet-skis, floating electric options are everywhere you look. In last summer’s issue of BV, we covered the Candela Seven electric speedboat from Sweden — almost for novelty value. It’s worth mentioning again because of its use of hydrofoils to reduce drag and improve efficiency — but it is far from being the only player on the waves.

Over in Seattle, Zin Boats is making the 20-foot, mostly carbon-fibre Z2R speedboat; it can go 100 miles on a single charge at a cruising speed of 15 knots. Its official top speed is around 30 knots (35 mph), but as company founder and designer Piotr Zin told TechCrunch, “We tested this boat to 55 [knots], but decided not to sell that to people. It’s just insane.”

This electric boat is as clean as it gets, too — there’s no pollution: zero oil, zero gasoline, zero anything getting into the water. Zin combines BMW batteries with a motor supplied by German company Torqeedo to power the Z2R. Torqeedo makes a full range of electric inboard and outboard motors with accompanying battery and charging systems, enabling the conversion of gas-guzzling boats to electricity.

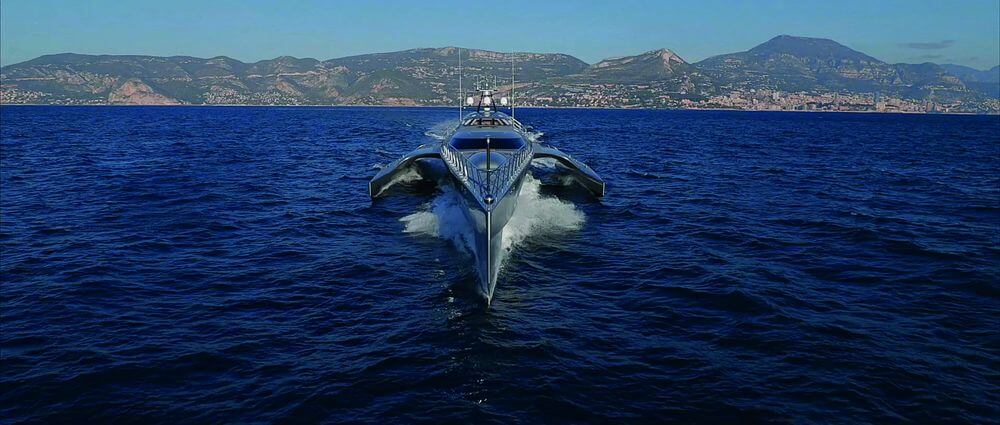

The Z2R has luxury trim, with a wood veneer and leather upholstery. This is reflected in its price of around $250,000, but we’re still a long way from the top end of the market, where the Power Eco range resides. These electric motor yachts are made by Sunreef in Gdansk, Poland, and while prices aren’t disclosed on the company website we found a not-quite-top-of-the-range 80 Power Eco listed for a cool €6m.

The most immediately noticeable feature of Sunreef vessels is the presence of solar panels covering every surface above the waterline: the sides of the hull and the sides and top of the superstructure, whether flat or curved. The panels are produced in-house and are the most efficient in the industry. Less than 1mm thick and weighing around 1.8kg/m2, they are flexible and can be moulded into almost any shape. This provides an impressive 68m2 of charging surface on even the entry-level 60 Power Eco, which can generate 13kWp (kilo-Watts peak per hour, peak meaning in ideal conditions). The 80 Power Eco has 200m2 of panels, generating 40kWp.

Sunreef electric boats are equipped with marine lithium battery banks exclusively developed for each model, almost 30 percent lighter than competing systems. They have an energy density of less than 6kg/kWh, equivalent to 167 Wh/kg. The company doesn’t provide range figures, other than to say that it is “unlimited at reduced speeds” — on sunny days presumably. The batteries are enough to power household appliances and air conditioning aboard — which presumably will affect the range.

Nico Rosberg, former F1 champion and Sunreef Yacht’s Eco ambassador, says that the manufacturer shares his commitment to sustainable technological innovation. “It is through the introduction of green technology and sustainable materials in the luxury sector that we create a halo effect on the entire industry,” he said.

The perennial bone of contention with electric vehicles is what to do with end-of-life batteries. Back in Sweden, two companies have united to convert a diesel boat to electric power using the old battery packs from two Tesla Model S cars.

The now-electric boat in question, the M/S Sylvia, was a Royal Navy vessel and dates back to World War II. The repurposed Tesla battery packs provide 190 kWh to the 85kW electric motor, and the Sylvia can cruise for 14 hours on a single charge — plenty for its six daily sightseeing trips around Stockholm. “No one is too small to make a difference,” said Eco Sightseeing founder Elias Nilsson. “I wanted to accelerate the development of sustainable shipping in close urban waters. In Stockholm, there has been talk of converting commercial vessels for many years. Talk and talk, but nothing has happened. I believe now is the time for action.”

Still on the subject of batteries, the UK’s OXIS Energy recently announced a $5m contract with Yachts de Luxe (YdL) of Singapore. BV readers will already be familiar with OXIS as battery supplier to Bye Aerospace in the US for its eFlyer range of electric planes. This new 10-year arrangement will see YdL working with OXIS Energy to develop a 40-foot luxury electric boat with a range of 70 to 100 nautical miles at cruising speed.

OXIS will supply a 400kWh battery system based on its Li-S cell and battery technology. As the company says, diesel pollutes and Li-S battery systems are a safe option for open water transportation. At the end of their useful life, the materials used in the Li-S cells can be disposed of without harm to the environment. OXIS Energy CEO Huw Hampson-Jones said: “The collaboration with YdL and the renowned French naval architect Jean Jacques Coste … allows us to provide a level of safety to our seafaring clients far beyond existing Lithium Ion battery systems.”

It isn’t just about luxury and fun. In March, the BBC reported on fishermen in Kenya swapping petrol engines for electric motors on Lake Victoria. As well as the reduction in pollution, the fishermen say the new way is cheaper, meaning they earn more. The engines are leased from a local company, and charging is included in the price.

As far as mixing with water goes, it appears that electricity is beginning to have the edge over oil.