Business magnate, visionary, philanthropist, investor, adventurer, film-maker, inventor and all-round eccentric: the man who did everything differently

ECCENTRICITY defined the life of business tycoon Howard Hughes, a man who would drive himself to the edge of madness with his obsessive desire to see his visions become reality.

Hughes lived a life of strange confusion, often sent into spiralling turmoil due to his severe Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) – a condition which few understood at the time.

Confusion was a recurring theme in Hughes’ life. No one knew exactly when he was born; he claimed to have come into the world on Christmas Eve 1905, but various records and documents suggest it could have been three months earlier. No documentation can pinpoint Hughes’ birthplace either – Houston or Humble are the likely candidates but the mystery of his origins only adds to the aura of myth that surrounded him over seven decades.

The youngster’s entrepreneurial spirit was fostered from an early age by his father, English inventor Howard R Hughes Sr, who had invented and patented the two-cone roller bit – a dull-sounding but ground-breaking piece of equipment which revolutionised the oil industry. It allowed rotary drilling to take place in previously inaccessible places, and helped to forge the US’s place in the oil business.

Hughes Sr was a shrewd businessman. Realising how important his invention was, he chose to commercialise it by not actually selling the bits he had patented. Instead, he leased the units and made a fortune in the process.

His father’s success sparked a deep fascination in science and technology for the young Texan, who began to show an increasing aptitude for engineering. At the age of 11 he built Houston’s first wireless radio transmitter and became one of the first licensed ham radio operators in America.

At just 12 years old, Hughes invented his own motorised bicycle, fashioned from parts of a steam engine his father had thrown out.

He became captivated by mathematics, mechanics and – above all else – flying. He was only 14 when he began flying lessons before going on to study aeronautical engineering at the California Institute of Technology.

The likeable young man was demonstrating all the signs of going on to become a great leader and pioneer in the field of engineering. But, while still a teenager, Hughes’ life was to change dramatically. His lust for life and passion for invention came to a halt when his mother Allene died through the complications of an ectopic pregnancy.

The death took a serious toll on his father’s health and, less than two years later, Howard Hughes Sr died of a massive heart attack.

It is said Howard Hughes never really recovered from the death of his beloved parents, but the tragedy did inspire his philanthropic activities. When he turned 19, Hughes was declared an “emancipated minor” and inherited three-quarters of his father’s sizeable fortune. One of his first acts was to establish a medical research laboratory in honour of his parents.

Slowly, the heir became more withdrawn. First, he pulled out of Rice University, where he had been showing great promise, then from various social circles where he had been the popular life and soul of many parties. He did keep up one of his great passions – golf. Often playing alone, he would spend almost every day on a course. On the rare occasions when he did feel sociable, he would play – to a notable three handicap – with some of America’s top professionals.

Eventually, his enthusiasm for sport waned and Hughes withdrew further into himself until, in June 1925, he married Ella Botts Rice – a family friend. Ella encouraged her new husband, who was becoming increasingly reclusive and gripped by OCD, to pursue his dreams of being a film-maker by moving to Los Angeles.

The move was a success, in terms of Hughes’ ambition for success as a movie producer. But it was a disaster for the marriage. By 1929 Ella had moved back to Houston and was talking to divorce lawyers.

At the time, Hughes himself was in the throes of producing Hell’s Angels – a World War I epic featuring some of the most daring aerial fight sequences ever filmed. Three pilots were killed during the making of the movie. Hughes became profoundly infatuated by the film, ploughing nearly $4m into it against the advice of many colleagues. No one expected Hughes to recover any of his investment, but in his own unique style he proved the detractors wrong when Hell’s Angels pulled in almost $8m at the box office and an Academy Award nomination for Best Cinemaphotography.

His marriage may have ended, but in Hughes’ eyes, his life was just beginning. Although continuing to suffer with OCD, he was less of a recluse. He made more movies, enjoyed more romances, made even more money, and soon began to develop visions of grand projects.

Soon after the success of Hell’s Angels, Hughes founded his own aircraft company. Typically, he immersed himself into every aspect of the business. Not only did he design planes, he would be in the factory at all hours, tinkering and fixing while construction was under way. He also insisted on testing the untried planes himself, often risking his own life.

Amid all the derring-do and attempts at world air speed records, there was also some genuinely brilliant business vision in his many innovations. For instance, Hughes is credited with inventing retractable landing gear.

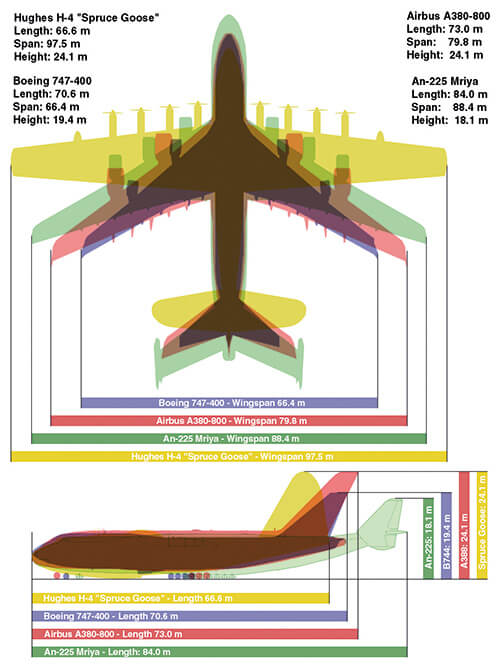

Then came the Spruce Goose. To many, the H-4 Hercules (it was given the name “Spruce Goose” by cynical members of the press) was effectively Howard Hughes’ Waterloo. He spent years labouring on the colossal wooden seaplane. His idea was to create a giant air transporter that could deliver troops and equipment across the Atlantic to the European theatre during the Second World War. He became so obsessed with trying to perfect the aircraft that he didn’t complete the project until 1947 – two years after the war had ended.

The aircraft flew only once, for a mile at 70ft, with Hughes at the controls. It was slated as a huge failure. His belief in the H-4 never faltered and, unable to let it go, he kept the giant machine in a specially-built, climate-controlled hangar. It remained there, in perfect airworthy condition, until his death in 1976. It is currently housed at Oregon’s Evergreen Aviation Museum.

Adamant the H-4 was the future of military transport, Hughes did not take the criticism at all well. He became deeply gripped by his OCD and began slipping back into the reclusive life.

In the days after completion of the H-4 project Hughes locked himself away in his screening room – a large cinema in his sprawling home – where he repeatedly watched Hell’s Angels and reviewed some of the movies he was producing at the time.

He remained in the screening room for four months, sustaining himself on little more than chocolate and milk. In contrast to the chronic OCD which had seen him unable to touch door handles or shake a stranger’s hand without scrubbing his own hands repeatedly, he did not bathe for the entire four months. By the time he emerged, his fingernails and grown into twisted spirals, his hair had become matted, and some of his teeth had rotted.

He rallied slightly when called to an antitrust meeting over Trans World Airlines – one of his many businesses – but he failed to attend. Instead, he chose to live in a series of hotel penthouses, locking himself away for months at a time and developing an addiction to Valium. At one hotel – the Desert Inn – he was asked to vacate the room. He refused, and instead bought the entire hotel before leaving for another inn just a few days later, on his own terms.

This self-imposed imprisonment continued until his death in 1976. As with the uncertainty of his birth, his death also came with a degree of confusion. The official report states he died at 1.27pm on April 5, aboard an aircraft en route to the Houston Methodist Hospital from his penthouse at the lavish Acapulco Fairmont Princess Hotel in Mexico. Many associates dispute this, claiming he died on a fight from the Bahamas to Houston. No one really knows why there should have been any sort of confusion, but it seems altogether fitting for Howard Hughes. He had, after all, lived a life of great eccentricity, bookended by confusion.

For many, the reclusive eccentric was the extent of the persona of Howard Hughes. It appears almost absurd that he could be considered a great business visionary.

Yet, here was a man – deeply troubled by his own demons and socially crippled by a condition that few understood – who was capable of making great and successful investments at which many had baulked. His Summa Corporation, as it later became known, spent decades at the forefront of industries like aerospace, media, hospitality, defence, electronics and manufacturing. His property portfolio was so vast that its true worth and total geography is still being calculated.

In 1972, when many of his companies and interests were brought under the Summa, much of his fortune was, at his request, bequeathed to philanthropic causes. Some were public, some were secret.

The Howard Hughes Foundation continues to create surprises with bequests that slip under the radar of the outside world. And that’s just how Howard Hughes would have liked it.