At around the time Abba were raising a glass of Babycham to toast their number one chart success with Waterloo, the good folk of 1974 were settling down for their weekly helping of Rising Damp or Porridge on push-button, black and white TV sets.

Meanwhile, nearly 5,000 miles away, there were some 450,000 people in a mysterious, land-locked, tiny kingdom who had never heard of Ronnie Barker or Leonard Rossiter. Nor were they familiar with Rising Damp, Porridge, Abba, Happy Days, The Rockford Files, The Osmond Brothers, Leeds United, Brian Clough, Harold Wilson, The Three-Day Week, or anything else that epitomised 1974 and dominated TV screens across Britain. In fact, they hadn’t even heard of television and, to be honest, it’s doubtful that there was any other reason for the people of Bhutan to know of Great Britain other than the fact that the British had intervened to free them from Chinese invaders many years before – twice over.

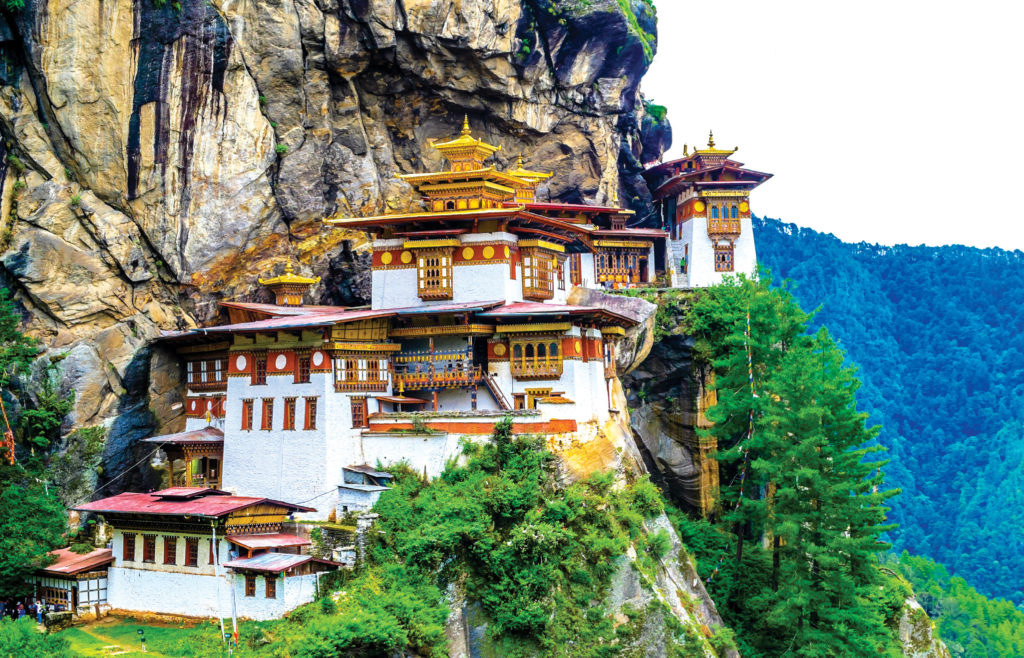

Yet, 1974, in all its bell-bottomed glory, marked a significant moment in the history of Bhutan. It was the year the first tourists were allowed into the curious country sandwiched between the borders of India and China. When those visitors strode across the border, little did they know they were helping Bhutan take its first steps towards becoming a remarkably influential force on the western world.

Furiously protective of its heritage and traditional way of life, there was little in the way of electricity in Bhutan. Most of its people were happy to be cut off from the outside world. Television and the Internet were banned throughout the kingdom until as recently as 1999. Yet somehow, less than two decades later, Bhutan is not only looking out at a world it didn’t want to join for most of its history; it is actually teaching advanced economies on how to be happy and prosperous. Bhutan has some explaining to do.

The Scene

Before tourists visited Bhutan, crime was unheard of. Apart from a bit of livestock rustling from a few roguish Chinese wandering across the border, the tiny nation had not even experienced so much as a whispered mention of a Friday night drunk and disorderly. In fact, even after tourism, relative peace had existed amongst the Vajrayana Buddhists up until the turn of the millennium.

No sooner had much of the world packed away its post-millennium Christmas decorations; minor infringements began to take place. Then, suddenly, three years after Bhutan became the last nation on earth to introduce television, the peace-loving Himalayan people – which by now had swollen its ranks to around 700,000 – came to know another modern-day phenomenon that quickly cast a shadow over the nation: a crime wave.

The king had at long last allowed television into his realm under a plan to modernise the country. It swept the nation like wildfire. From nothing more than homemade entertainment to over fifty of Rupert Murdoch’s finest cable channels overnight – the population went mad for telly. Quite literally.

By April 2002, Bhutan was awash with theft, violence, drunkenness, fraud, and even murder. There wasn’t much of a word in the Dzongkha language for corruption, but, on April 13 of that year, 42-year-old Parop Tshering – chief accountant of the State Trading Corporation – was hauled before a court charged with the embezzlement of four and a half million ngultrums (just shy of £70,000). At the same time, the suddenly overworked Royal Bhutan Police were out in force in the town of Mongar where thieves had smashed up and robbed three ancient Buddhist temples. For an entirely sedate Buddhist nation, things had become too heady.

Yet, the final straw came a few days later. In Thimpu, Bhutan’s serene capital, a 37-year-old truck driver named Dorje was discovered by his wife as a heroin addict. Enraged at being found out, Dorje bludgeoned his wife to death. Soon after, in a nearby village, a 42-year-old farmer called Sonam was driving to his family home. His in-laws were in the car and, smelling alcohol, began complaining about Sonam’s erratic driving. The farmer became so enraged that he steered the vehicle off a cliff. The crash killed his niece and badly injured every member of his family. That, as far as the king was concerned, was quite enough.

Back to Basics

The king called upon his government to put an immediate stop to the moral decay. While taking away the phones, the televisions, and the Internet would have been relatively easy, it could have sparked the ire of the public. Instead, authorities opted for a re-education campaign.

People were reminded of – if not bombarded with – the very essence of their land and the reason why it exists. The country was founded as a Buddhist sanctuary in 1616 by Shabdrung, a monk from nearby Tibet. The land was remote and, aside from a couple of invasions in the 17th and 18th centuries – duly repelled by the British – few people knew of Bhutan. In fact, it was only after the 1937 film Lost Horizon (based on a James Hilton novel) that the country’s existence even crossed people’s minds. In the book, and the film, Bhutan was portrayed as Shangri-La – a mysterious Himalayan land where the people barely aged under the mantra of a high lama who declares: “Here we shall stay with our books and our music and our meditations, conserving the frail elegancies of a dying age.”

It was those words which the Druk Gyalpo – or Dragon King- Jigme Singye Wangchuck recalled as he began the process of returning Bhutan back to the peace and tranquillity it had once known.

The royal mission was crowned with success. People began turning their back on television and the worldwide web which they suspected of undermining their culture. Normality soon returned, as did their way of life. The birth rate, which had slowed noticeable after television’s arrival, picked up again.

Ten years ago, with peace and tranquillity restored, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck abdicated in favour of his son Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. He charged the then 26-year-old to lead Bhutan into the modern age. Both father and son agreed that their country’s place in history was to teach the world about harmony and happiness. It was a task the youthful leader embraced with aplomb.

GNH Replaces GDP

The seeds of happiness were planted in 1971 when the king and his government announced they would not recognise the gross domestic product (GDP) as a barometer for measuring progress. Instead, Bhutan had a different gauge for testing its performance – GNH, or Gross National Happiness. GNH collates information on the physical, environmental, and spiritual health of the population.

The GNH – aka happiness index – works for Bhutan, a place well-suited for the pursuit of tranquillity and spiritual well-being. Of course, being a nation that flew well below the global radar, it would be years before the GNH was recognised by any of the world’s economic powerhouses.

It took a global economic downturn before the unique approach of this tiny Buddhist nation began to attract interest.

The Netherlands was the first country to take note of Bhutan’s unique perspective. The Dutch signed a bilateral Sustainability Treaty with the country in 1994 which forged a relationship based upon equality and reciprocity. The treaty developed strongly and led to solid ties between the two countries. Amongst many other projects, Dutch engineers were largely responsible for the rural electrification programme rolled out across Bhutan, and Dutch artists helped expand and develop Thimpu’s School of Fine Arts.

Heading in the opposite direction was Bhutan’s participation in the massive Zeeuwse Vlegel project which was a determined effort by The Netherlands to pioneer organic farming. Bhutan’s centuries’ old natural approach to agriculture – which remains the main livelihood for more than 60% of its population – had a big role to play in setting the benchmarks for the scheme, which continues to this day.

This little country’s highly original approach to commerce isn’t just generating widespread happiness for itself and its trade partners, it’s also delivering serious wealth. While it may seem somewhat hypocritical of a nation which extols well-being over riches, it’s fair to say that Bhutan is now enjoying the best of both worlds.

With a political agenda built around conservation and sustainability, and a concerted effort to write a constitution based on health and learning, the life and wealth graphs of Bhutan are remarkable. In the last 20 years, life expectancy has more than doubled; 98% of all children in the country are enrolled in school; and, as an average, almost every family is around a third better off than two decades ago.

Until the End of Time

Environmental protection – an expertise adopted early by The Netherlands and currently catching the eye of other European heavyweights – is second nature to the Bhutanese. Their government recently signed a pledge to ensure that 60% of the country’s landmass will continue to be nothing but forest “until the end of time.” Hand in hand with that pledge, timber exports are banned, and a monthly Pedestrian Day was introduced when all vehicles are banned from the roads.

Some of the Bhutanese policies may soon be coming to the UK. A delegation of government officials and, potentially, a visit from King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck are on the cards for late 2016 or early 2017. It is understood the monarch not only wants to promote his country’s way of life, but also wishes to revisit Oxford University where he spent several years studying politics and international relations. It was this desire for learning that has made the ruler so instrumental in getting the youth of Bhutan to actively pursue education.

Leading the charge for Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck is his impassioned Minister of Education Thakur Singh Powdyel, also one of his king’s greatest advocates of the Gross National Happiness Index. “It’s easy to mine the land and fish the seas and get rich,” Mr Powdyel once declared at the height of the recession. “Yet we believe you cannot have a prosperous nation over the long run that does not conserve its natural environment or takes care of the wellbeing of its people, which is borne out by what is happening to the outside world.”

Dutch ties with Bhutan have loosened a little as other economies began to develop an interest in the Buddhist nation, although Bhutan is keen to uphold trade links with the first European country it established diplomatic relations with. Since becoming involved with The Netherlands in 1985, the Himalayan outpost has kept the carefully selected group of nations with which it has diplomatic ties to a minimum.

The Dutch help underwrite Bhutan’s economic development with several programmes such as the Facility for Corporate Social Responsibility and Food Security, the Development-Related Infrastructure Investment Vehicle, the Entrepreneurial Development Bank, the Centre for the Promotion of Imports from Developing Countries, the Netherlands Senior Experts Programme, and Bhutan+Partners – a non-governmental organisation based on the edge of the Veluwezoom National Park in The Netherlands that promotes the interests of Bhutanese and Dutch companies.

Around €2m a year is spent through the Netherlands Development Organisation on agriculture, forestry, renewable energy, sanitation, and hygiene. The body has invested almost €25m in Bhutan since 1988.

With years of investment – both financial and intellectual – from The Netherlands, Bhutan is now a well-equipped to claim a spot on the world stage. At the epicentre of happiness – the ultimate sustainability benchmark – the country has become the darling of development agencies worldwide.