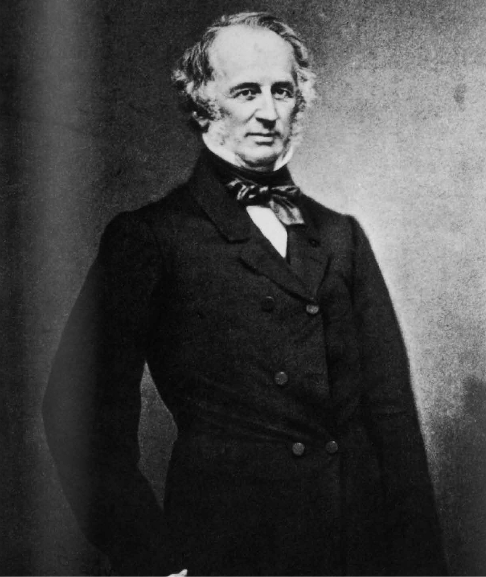

He was the man who Americans loved to hate, yet his achievements were revered. Selfish, unfriendly, single-minded and with a merciless desire to beat anyone who challenged him – was Vanderbilt not the very epitome of the American dream?

‘Control the market, control the profits’. It’s a cold-blooded philosophy but it’s one which many ruthless success stories are often built upon. It’s also the law by which Cornelius Vanderbilt – the original tycoon and one-time America’s richest man – lived his entire life.

Vanderbilt lived to compete. It defined him. It was present in everything he did. But there was one thing more dear to him, something that outshone his constant desire to compete… the need to win. And win he did. By fair means or foul, this enigmatic New Yorker would do anything to satisfy his burning lust for victory.

Cornelius was born into the Vanderbilt family of Staten Island on May 27 1794. They lived a fairly hand-to-mouth existence with few possessions, and even fewer prospects. As a child, Cornelius was unhappy being poor and would often talk about his plans to better himself as soon as he left school. None of his teachers would have had much faith in his ambitions though – he simply showed no interest whatsoever in education, barely scraping by with the ability to read and write.

At the age of 11, he was given an opportunity to quit education. He didn’t hesitate. He ran from the school grounds and straight to his father’s boat which Cornelius Snr used as a small ferry in New York Harbour. The youngster loved the life of a ferryman – being paid to float people and goods from place to place appealed to him. Transport was something he saw as being one of the wonders of the modern age – an adventure that would be dripping in both potential and money.

He quickly caught on to a trick that would allow his father’s boat to have the pick of the day’s jobs. Instead of going home at the end of the working day, he would moor his father’s boat in Manhattan and then sleep on board in order to be the first and only boat at the docks when people and goods began to queue for transportation the next day. By the time his father arrived for work, Cornelius Jnr had already filled the boat’s coffers.

Before long, Vanderbilt had enough cash to purchase his own boat. By the age of 20, he had a small fleet and acquired a nickname from the elder seafarers of the harbour. They called him ‘The Commodore’ – a moniker that would stick until his dying day.

He was also one of the first boat operators to embrace the age of steam power. Stealing a march on his contemporaries, he even began to construct his own steamships as well as buy up the first of the craft to be built in New York’s shipyards. His grip on the market was ever tightening.

He would stay up all night hatching plots on how to control his market and maximise his profits and, as iron-fisted and merciless as he was, he dreamt up a killer stroke of financial genius. By slashing his fares he preyed upon a mobile American public keen to watch their pennies. In turn, his undercutting bullied his rivals towards bankruptcy, allowing him to buy them out at knock-down prices.

By the time of the American Civil War, Vanderbilt was on the brink of total monopoly over steamship travel between New York and Boston. He even loaned his biggest and fastest vessels to the Union Navy for their pursuit of Confederate commerce raiders. On August 20, 1866, hours after President Andrew Johnson signed the Proclamation of Peace, he was also signing off an enormous bounty as a reward for Vanderbilt’s assistance in the conflict.

With even more money swelling his already burgeoning vaults, Vanderbilt looked for his next source of outrageous wealth. It didn’t take him long to grasp the importance rail travel across a vast land, recently divided by war, would have in the rebuilding process of the United States. Before long, he controlled all the lines, trains and rolling stock between New York and Chicago. From there, he began to play the markets.

Regularly risking vast sums of money in order to reap quick rewards, Vanderbilt slowly began to grow into the most dominant force on the stock exchange. He taught himself how to manipulate stock prices and shift unimaginable amounts of money between companies, all the while channelling more dollars into his own personal fortune.

In 1869, Wall Street was on the verge of panic. Vanderbilt moved to arrest the potential meltdown by buying up companies on the verge of failure and pumping millions of dollars into them, then flooding the market with shares in his own railroad. Sadly, his motivation was nothing to do with rescuing the US economy, it was purely down to greed and the desire to scupper the plans of a sworn enemy – Jay Gould – who was attempting to corner the gold market.

At first glance, Vanderbilt’s actions in 1869 had made him look like a hero. But on closer inspection, his bitter rivalry with Gould triggered the original Black Friday and left hundreds of investors and businesses utterly ruined. There was only one significant winner from Black Friday – and that was Vanderbilt himself.

No one really knows just how much Vanderbilt profited from his battle with Gould. Nor does anyone know how he escaped investigation when others were hauled down for much lesser roles in one of Wall Street’s darkest days.

Following Black Friday, he continued to play the markets, bullying and dominating in his usual style. He fathered 13 children, giving each of them a business of their own, yet cutting them off if they showed signs of daring to fail. As if playing up to his cold and unforgiving reputation, he also made a point of being ferociously uncharitable. The one occasion when he did give money away was as a donation to build a university in Nashville in 1873. It still remains today, named, as the agreement always stated it should, ‘Vanderbilt University’.

When Vanderbilt died on January 4 1877, at the age of 82, he owned about one eighth of all the money in the USA – $105m. It may not sound like a colossal sum, but, in today’s terms, it equates to around $2,333,296,875. Not bad for a boy who could just about read and write, and taught himself maths as he ferried passengers around a harbour.