BV’s JASON AGNEW takes a look at the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 1: the bid to end world poverty

INDIAN political and spiritual leader Mahatma Gandhi once said: “Poverty is the worst form of violence.”

While India has greatly reduced its levels of destitution, and much of the country would be unrecognisable to Gandhi in 2020, there are still over 70 million people living — or existing — in extreme poverty.

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were set by the United Nations´ General Assembly in 2015, designed to be a “blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all”. The ambition is to achieve these goals by 2030.

SDG1: to end poverty

SDG1 aims to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere”. Extreme poverty has been more than halved in the last 20 years — but one in 10 of the planet´s population still has to survive on less than $1.25 a day.

Worldwide, the poverty rate in rural areas is 17.2 percent — more than three times higher than in urban areas, which explains the global exodus from the countryside, and the rise of the megacity.

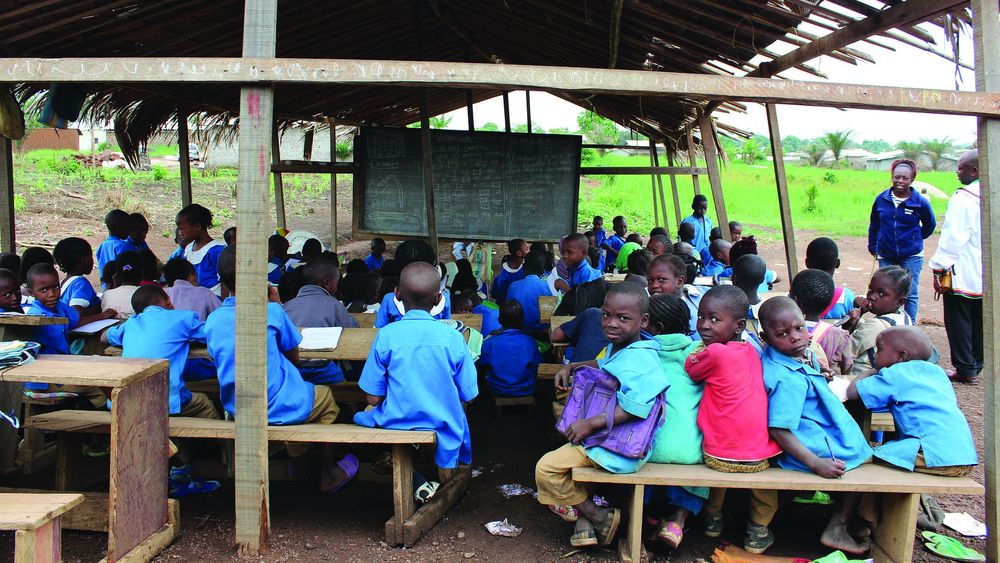

Poverty does not just refer to a lack of income or resources; it encompasses healthcare, education, and security. Despite it being widely accepted that children constitute the majority of those living in extreme poverty, 63 percent of countries have no data specific to child poverty — and a staggering 97 percent have insufficient data to make viable projections towards Goal 1.

Having a job certainly doesn´t save you from abject misery; in fact, eight per cent of the world’s workers and their families were living in extreme poverty in 2018.

So how have some of the major companies embraced these goals, not as an exercise in philanthropy but as a means of preservation for the marketplace of the future?

As the chief marketing officer of Unilever, Keith Weed, wrote in The Guardian: “The brands that have not yet caught on to this, and are not thinking about how they will embed environmental and social sustainability within their business model, will not be around in the next 50 years.”

Financial services company Visa is addressing SDG1 by reaching out to under-served markets, to 500 million of the two billion “unbanked” adults with no or little access to financial services because of poverty or where they live. Electronic payments have become an important tool in helping people, especially those in rural areas, to avail themselves of such services. By empowering new consumers, a company is creating a whole new client base for itself.

The UNGSII (UN Global Sustainability Index Institute) was created to support, accelerate and monitor the implementation of the SDGs, evaluating and comparing sustainability performance of companies, cities and countries in a transparent manner.

Its Commitment Report considers the top 100 blue chip companies. Of those 100 with a combined market cap of $9.781tn, 82 disclosed their commitment to the SDGs in their 2016 annual reports. The results were not surprising: Volvo came top, Novartis second and Sainsbury third in terms of visibility, i.e. how many statements in their annual reports refer to the SDGs. US giants such as Walmart, Boeing and Apple didn’t make mention of the goals in their reports, although this is not necessarily indicative on their sustainability policies.

The problem for SDG1 is that with such a broad, ambitious goal, it is hard for companies to know where to start. If you’re a renewable energy company, your first instinct on looking at the SDGs might be to think, “Great, we are contributing to SDG 7 (clean and affordable energy) – and that’s our role in the SDGs sorted”. Companies assume that SDG1 doesn’t apply to them — and that is one of the major reasons why it is ranked as a “low-priority goal” for the business community.

The lack of specificity makes it easier for firms to identify with more narrowly focused SDGs and finding solutions for Climate Change, Gender Equality, and Reduced Inequality have been identified as the top SDG priorities for corporations. This means that SDGs 5,10 and 13 are much easier for companies to prioritise whereas the eradication of poverty tends to be viewed as the responsibility of governments.

A good example of commitment to SDG 1 comes from Myanmar, where in 2015 the government was proposing to create a minimum wage of $2.60 a day for workers. Garment manufacturers in the country were proposing an opt-out for their industry. But 30 European companies — including Tesco and M&S — wrote to the Myanmar government opposing the suggestion on the grounds that it would deter them from investing in the country. The government duly forced through the new base wage.

Such actions can lift thousands, even millions, out of extreme poverty, and relatively quickly at that. The UN probably cited No Poverty as its prime objective because achieving that would lead to other sustainable development goals becoming achievable.

That, in itself, makes SDG1 an extremely worthwhile aim.