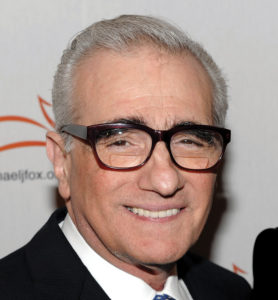

If Martin Charles Scorsese hadn’t made the momentous decision to become a film-maker, he would have joined the priesthood. A celibate life of serenity in the Roman Catholic church seems a far cry from his chosen career path, especially considering that his body of cinematographic work contains a fair measure of profanity, violence, gang culture, greed, and other decidedly sinful pursuits.

If Martin Charles Scorsese hadn’t made the momentous decision to become a film-maker, he would have joined the priesthood. A celibate life of serenity in the Roman Catholic church seems a far cry from his chosen career path, especially considering that his body of cinematographic work contains a fair measure of profanity, violence, gang culture, greed, and other decidedly sinful pursuits.

Rumour has it, Mr Scorsese actually got expelled from the Upper West Side Cathedral Preparatory School and Seminary where was enrolled in 1956 at the age of 14. He’s never admitted it publically, but friends say the young Scorsese soon discovered girls and became distracted by rock and roll before taking his vows.

Imagine a world without Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, The Departed, or Goodfellas. It is not unjustified to consider Father Marty’s lost contribution to civilisation somewhat less relevant than that of Martin Scorsese – father of the movie industry. Even then, with some of the most notable pictures made in the last fifty or so years, one would only be scratching the surface of Scorsese’s work.

Just like one of his brooding characters – usually obsessive and haunted, looking for inner peace, and redemption as their world crumbles – there’s much more to this man than meets the eye. Mr Scorsese is not just about making thought-provoking movies packed with bleak irony and moral ambiguity; he’s also keen to make the world a better place.

Unlike some of his contemporaries – those Hollywood elite types with more money than brains and always eager to embrace a cause for appearance sake – Mr Scorsese is not about spin, smoke, or mirrors.

Mr Scorsese’s early life resembles a script for one of his films. His Sicilian grandparents moved to the US seeking a better life, living in New York. He spent an early childhood in Queens – one of the city’s toughest boroughs – before moving to Little Italy in Manhattan. As a youngster, Martin Scorsese was always at a disadvantage. He was the shortest in his class and was often ill.

Chronic asthma would keep the young Scorsese indoors for much of his childhood, and it was this confinement away from the playgrounds and sports fields that led his father, Charles, to start taking him to the cinema every week. It is where Mr Scorsese’s love affair with the silver screen began.

Aside from his short detour into theology, he graduated from NYU in 1964 with a fine collection of student films under one arm. Mr Scorsese quickly worked with the young Harvey Keitel and Francis Ford Coppola, before a collaboration with Robert De Niro lit the blue touch-paper under his career. The rest is history.

Keen not to be defined purely as a director of violent and edgy films portraying the darker side of American life, Martin Scorsese should be credited too for his humanitarian work. Few people are aware of his charitable contributions; fewer still know precisely to what causes he devotes his private time. That’s a measure of the man, in that he’s not consumed by a need to tell the world how he deploys his wealth and influence – he just gets on with it.

One cause that he has proudly pinned to his sleeve, however, is trying to curtail America’s problem with gun crime. There seems to be a strangely twisted irony about a man whose movies portray so much violence wanting to help stem the tide of firearms.

Mr Scorsese has thrown his weight and wealth behind the One Less Gun charity which is committed to decommissioning firearms left behind in warzones and, closer to home, in the aftermath of crimes. Each time a gun is depicted in his films, he makes a donation, and he’s urging other directors to show the same largesse.

Observers will note Mr Scorsese started leaning away from violent gang movies and is, instead, focusing more of his attention to epic music documentaries – particularly on his personal obsession with the Rolling Stones who he credits with delivering a soundtrack for almost every chapter of his life.

In his own words, he wants us all to learn to love one another a little more: “Violence is not the answer, it doesn’t work anymore. We are at the end of the worst century in which the greatest atrocities in the history of the world have occurred. The nature of human beings must change. We must cultivate love and compassion.”