Are advancements in 3D technology about to herald the start of a new industrial revolution?

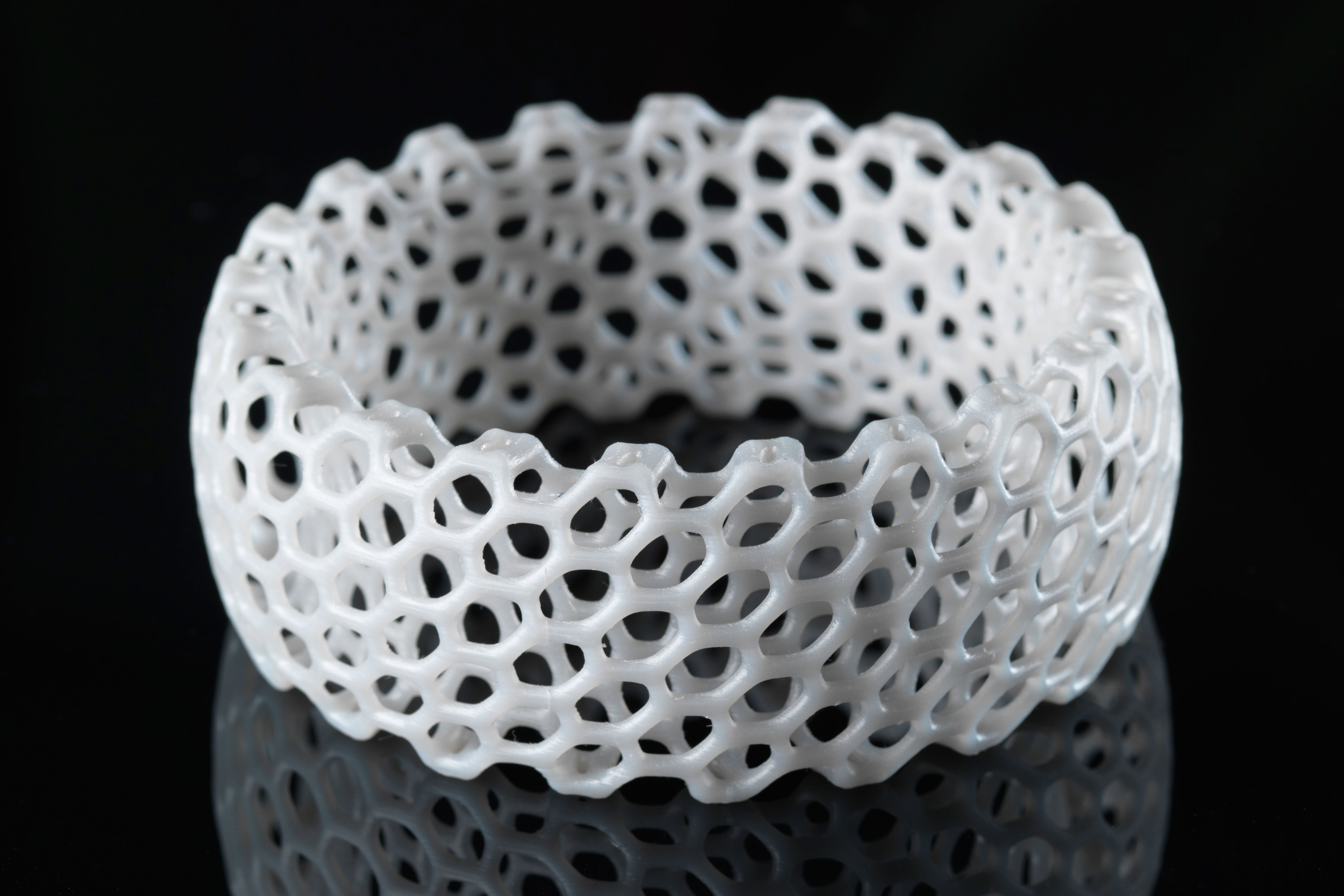

THE latest essential accessory for technology fans is, without doubt, a 3D printer. These easy-to-obtain devices can be used to impress friends, colleagues and family by rustling up customised plastic models, jewellery, toys and gadgets.

Out in the wider world of industry and commerce new 3D printing technology may bring about a revolution in manufacturing techniques. Personalised and distributed manufacture could replace a system of mass production in centralised factories creating specific parts. Instead of ordering a stock item for delivery customers looking for a replacement component will soon be able to download the template from an online catalogue and manufacture the part locally using a sophisticated, next-generation printer.

Additive manufacturing (AM) or 3D printing has nothing to do with paper and ink. The terms describe a range of technologies which use computer control to lay successive layers of material to precision-build a three dimensional object. The manufacture, or ‘printing’ processes, are controlled using digital data. Over the last few decades, 3D printing processes have evolved to such an extent that a variety of additive processes are now available. Some processes build parts by extruding molten plastic through a nozzle and precisely depositing this onto a build platform. Other technologies use lasers to melt layers of powdered material, while other techniques use ink-jet printing heads to deposit material into the shape of the desired component part.

A wide range of raw materials can be deployed, but as each substance has a different melting point they can only be used in printers that provide the appropriate extruder temperature. Small, domestic scale 3D printers can be bought for less than £1,000. They usually use Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) techniques, melting and extruding plastic filament which then solidifies to form the object.

Interestingly, the companies developing the technology and machinery for the new equipment did not come from a print background. They emerged from the plastics industry and from research institute spins-offs. Developers included Stratasys, Z Corp, Makerbot and 3D Systems.

Much inspiration came from the 2005 RepRap Project – an open-source initiative to create a 3D printer that could produce most of its own parts. At the time, the big-name printing companies did little more than look on from a distance. However, that looks to be changing with print giant HP recently announcing that it hopes to bring its first 3D printers to market. It says it wants to drive the ‘next industrial revolution’ and spark a change in the way products are manufactured. The company intends to use its own multi-jet technology and target the commercial market.

Not everything to do with 3D print technology has been welcome. The frightening prospect of home-printed firearms loomed large recently when a design for a firearm was put online in the US along with a 3D printable rifle and a magazine for an AK-47. The government ordered the blueprints to be taken down, but, as is the nature of the world wide web, the genie is out of the bottle and the designs continue to be available. US legislators continue to wrestle with the challenge of framing laws to prevent access to designs for home printing firearms whilst not infringing Americans’ right to bear arms. In May 2014 Japanese police arrested a man for possessing five printed guns. Although he had no ammunition two of the weapons were capable of being discharged.

Industrial uses of 3D printing set to soar

Advances in AM technology mean that it is possible to build intricate shapes even from complex metals such as titanium or aluminium by using lasers to melt metal powders. The technology enables manufacturers to deliver accurate and cost-effective low-unit volumes.

Companies initially used 3D printing to make prototype parts and products, benefitting from reduced lead times and development costs. Major manufacturers including GE, BAE Systems and Siemens use the technology in high tech automotive and aerospace industries.

Combining 3D scanning with 3D printing makes it possible to swiftly and economically manufacture replacement components that may be long out of production. For example, in the power industry, heavy plant may have a 50-year operational life. The original specifications and design of components may be missing, but reverse engineering can be used to make a digital 3D image of the component which can then be replicated in a printer.

Sellafield, in the north west of England, is Europe’s largest and most hazardous nuclear complex. Many of the facilities are over 50 years old and were one-off designs using custom-manufactured parts. Records and documentation of the equipment may be non-existent or inaccurate. Procuring replacement parts by traditional means is both expensive and time consuming, leading to delays and temporary plant closures. The site operators are keen to explore the potential for using the new technology. A large cost saving was made when a new lid for a 40-ton nuclear waste export flasks was 3D scanned to quickly and accurately recreate the geometry of what is known as a ‘legacy component’. The scan cost about £3,000 compared to the £25,000 it would cost using conventional methods. The new part was then printed using digital technology.

Materials development is seeing lighter, tougher and stronger composites coming on to the market. The combination of new materials and additive manufacturing techniques could transform the way that things are made. In the healthcare arena various replacement body parts are made by additive manufacture. Printed parts are used in dental work, hip replacement surgery, knee implants, cranial patches and facial implants used in reconstructive surgery.

While 3D printing might be seen as merely the latest technology gimmick, it has the potential to transform industry. Designers, engineers, artists and researchers are finding new uses for 3D printing every day. Just as in the fifteenth century when the invention of the printing press revolutionised communication and led to the spread of knowledge, 3D printing could herald a revolution in manufacturing of components for high tech industries.