Americans love their heroes; the loners and outsiders who take on the meanest, most black-hearted baddies, and beat them single-handedly.

Who knows if Steve Jobs saw himself as a hero? He certainly worked hard on his image throughout his life, and he possessed the necessary streak of ruthlessness, combined with a splash of sentimentality, to succeed – recognisable traits in many of history’s great heroes – and monsters.

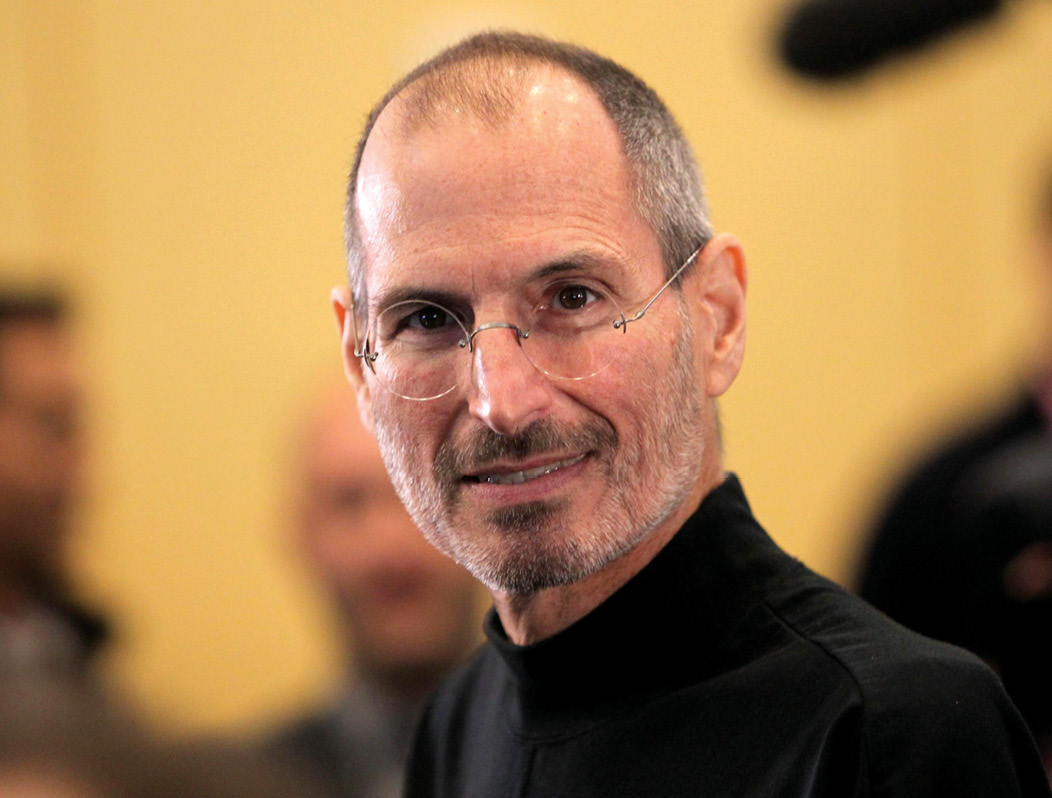

Dressed in a black gown over pale blue jeans and scruffy sneakers, Steve Jobs looked like an academic version of Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name when he rose to address a crowd of eager undergraduates in an open-air Stanford University Commencement ceremony in 2005.

The youngsters whooped and hollered. Here, with his close cropped hair, fashionably stubbly grey beard, and wire-rimmed specs, was their Wild West Hero – inscrutable behind narrowed-eyes, he was the essence of the gunslinger.

On reflection he was also, like the archetypal western hero, fatally wounded at the time, holding at bay the cancer that would kill him within a few years.

His speech to those undergraduates has been viewed millions of times on You Tube, achieving close to mythological status. In reality, it was a run-of-the-mill delivery of a standard message, given poignancy in hindsight. His own inevitable demise must have been on his mind when he told the students: “Your time is limited. So don’t waste it living someone else’s life”.

Steve Jobs’ life story even reads like the script of a Western: he is abandoned at birth, taken in and raised by a homely American family, and went on to have a troubled youth. However, the young loner wins the love of his hometown sweetheart, and achieves rapid success. When this is snatched away by the men in black hats, he goes into the wilderness where he finds the strength and courage to rebuild and fight back.

In the final act, he comes home to claim his birth right and exact revenge on the bad guys, earning the adoration and respect of the humble townsfolk. The film would end, predictably, with tears as our hero, having achieved all his goals, rides off into the sunset.

Stripped of all the complexities, this was the Steve Jobs story. But the real narrative, as always, is hidden somewhere in those intricacies. There is a long cast of fellow players who might take issue with the legend.

Steve Jobs’ own heroes were Einstein and Gandhi – giant photographs of the pair were practically the only adornments of his famously minimalist apartment in New York. This points, perhaps, to a desire to be seen, not only as a genius, but a genius with a soul who wants to bring freedom to the world.

Meanwhile, Apple customers were being ushered, blissfully unconscious, into a gilded cage. Apple provided shiny trinkets which appealed directly to lovers of hi-tech fashion, and then locked them into a life-long relationship with the company. That was true genius.

Jobs has been criticised for somehow manipulating Apple customers into buying style over substance, but the whole history of the development of the personal computer has been about selling something that people didn’t know they needed. And in the 1970s, did anyone really need a home computer?

Every business has to adapt in order to survive and prosper, especially in the rapidly-changing world of new technology where nothing ever remains static. Apple’s troubles in the late 1980s appeared to begin when, having grown to respectable corporate size, it evicted the inventive but volatile Jobs in favour of John Sculley – an apparently safe pair of hands from a conventional corporate background. The company promptly went into a steep decline. It was rescued, and reached new heights, when Jobs returned and developed the iconic stream of gadgets that changed its fortunes – the iMac, iPod, iTunes, iPhone, and iPad. A cash injection from the friendly folk at Microsoft kept Apple afloat and allowed Jobs time to work his magic.

Jobs’ reinstatement at Apple, and his subsequent triumphs, appear to confirm the man’s status, but could anyone have done what he did? Again, he was lucky in having the inspirational British-born designer Jonathan Ives at his right hand. But was that luck, or excellent judgement?

His talent for seeing things in a different way to ordinary people was first demonstrated in his Dad’s garage in suburban Los Altos, California, in the 1970s. That ability extended to the people around him. His first business partner, the likeable nerd Steve Wozniak, was the gifted one when it came to building computers. It was Jobs, though, who saw the commercial potential – and it is the far-sighted visionaries who are ultimately remembered by history.

Apple is often described as more of a religion than a business. Its customers are dubbed Macolytes and Steve Jobs, even in death, is their Messiah. Apple stores are defined in terms which might shame a cathedral. And Jobs certainly had a spiritual side, but who knows how much of that was born of the wacky West Coast climate of drugs and mysticism in the seventies?

He spent some time in India as a young man, worshipping at the feet of various gurus. Like many fellow long-haired youngsters who followed the hippy trail to the East, he returned and soon swapped his mystical robes for the conventions of Silicon Valley. Zen and the art of world domination, perhaps?

If Steve Jobs is remembered as a heroic maverick, his nemesis, Bill Gates, is the preppy college boy who achieved success despite, according to Jobs, his “lack of imagination.” Today, Apple and Microsoft are technology giants straddling the globe, but they’re as different as the personalities of Jobs and Gates.

Gates is the wide-eyed and friendly geek. His achievements, though they helped change the world, lack the drama of Jobs’ rise to fame. Jobs once famously launched a lawsuit against Microsoft for copyright theft. Gates, characteristically droll, described the claim as one burglar moaning that another burglar had stolen something before he’d had a chance to steal it himself.

It might be argued that the enmity between the two was rather one-sided. Jobs was an obsessive, and viewed the world in black and white. Gates, on the other hand, was a pragmatist. Indeed, Microsoft came to Apple’s rescue in 1997 with a $150 million investment which helped breathe new life into the ailing giant at a crucial period. Hardly the action of a cut-throat rival.

Steve Jobs may be remembered as the hippy who created one of the world’s biggest corporate beasts, but those gunslinger’s eyes hid a complicated human being.

His first companion, Chrisann Brennan, gave an indication of his character in her book, The Bite in the Apple: A memoir of my Life with Steve Jobs. At one fractious meeting, she recalled: “Steve touched my forehead to indicate that I was his, which I found outrageous.”

One of his designers at Apple remembers that Jobs was difficult to work for: “He had an uncanny capacity to know exactly your weak point, know what would make you feel small.”

When Jobs worked as a teenager for Altari, its boss, Nolan Bushnell, noted that he was “difficult but valuable,” adding, “he was very often the smartest guy in the room, and he would let people know that.” Almost everyone who came across him had an opinion, good or bad – frequently bad. Fortune Magazine described him as “one of Silicon Valley’s leading egomaniacs.”

And yet, at times his modesty could be glimpsed. “There’s many things in life I don’t have the faintest idea what I’m talking about,” he once admitted. In Brennan’s frank memoir of her life with Jobs, she remembers the moment their daughter, Lisa, from whom Jobs had been estranged, decided to change her surname to incorporate his name. “Steve told me that he could hardly believe that she wanted to take his name. Very plainly relieved and honest, he said, ‘I am just so happy that she does.’”

By dying at the height of his triumph at the pitifully young age of 56, Steve Jobs has guaranteed his place in history. And, for better or worse, the world he helped create is a very different place from the one he was born into in 1955.

In 1985, Jobs invested in Pixar, a fledgling graphics company. It was probably one of his simplest and shrewdest bits of business, and it earned him billions of dollars. The company was filled with creative minds, a fact which Jobs recognised with his renowned ability to spot a potential no-one else could see. Pixar subsequently evolved into a globally successful maker of blockbuster animated films – including Toy Story.

Did Steve Jobs get lucky, being in the right place at the right time, with the right friends? Or did he really know what he was doing when he created, was rejected by, and then restored Apple to its position at the top of the pile? Nearly five years after his death, that question is still being asked.

The folk singer Joan Baez, who had a two-year relationship with Jobs, said: “Steve had a very sweet side, even if he was erratic.” So, a little bit of the good, the bad, and the ugly – part Pale Rider, and part just loveable old Woody from Toy Story.